September-December 1966 Continue reading

Classes: I took four classes. Each was memorable in its own way.

The math department had three sequences that math majors could take. Two were for students in the honors program. I took the higher honors sequence—six classes over three years with the same classmates.

Our teacher was Professor D.J. Lewis1. The class consisted of about twenty guys and one girl. I don’t remember any names. Dr. Lewis began by saying that there were two ways to teach math. One was to go through the proofs at a fairly brisk pace. The other was to make sure that most people were comfortable with each concept before moving on to another. He said that as a student he much preferred the latter, but when he looked back on it, he learned more from the former method. So, all through the class he filled the blackboard with formulas. I went to every class, or at least nearly every class, and I did get quite a bit out of them.

The Russian teacher was Mrs. Rado. I had the advantage over the other students of knowing the Greek alphabet, which is similar to the Cyrillic alphabet. My primary disadvantages was that all my language experience was in dead languages. In high school we learned how to translate Latin and Greek, but not how to speak or understand them. I had to spend quite a bit of time memorizing and rehearsing the conversations. Fortunately, I had the time and inclination to do it. By the end of the semester she referred to me as the “отличник“, which was a little embarrassing, especially since most of the other students were older.

I also remember one class in which I was repeatedly asked by Mrs. Rado to pronounce the Russian word for five (пять). I never did it to her satisfaction.

The class that I was worried about was chemistry. I was enrolled in Chemistry 103, which, according to the catalog, was for students who did not take chemistry in high school. When I found out that the vast majority of my classmates had indeed already taken chemistry, I was ready to panic. However, it turned out that the subject matter was very easy—basically just a lot of permutations of Boyle’s law, PV=nRT.

I was lucky to have a lab partner who knew his stuff. I don’t remember his name, but he taught me, among other things, the use of the MIT Fudge Factor, which is .9677. He explained that if you were unable or unwilling to complete an experiment, begin by calculating the correct answer. Then, multiply or divide by the MFF. That is what you report. If you multiplied last time, divide this time.

We only needed this technique once, when he decided to augment the assigned experiment with some creative glassblowing over the Bunsen burner. Unfortunately, he accidentally bumped the beaker containing our unweighed sample with his still white-hot objet d’art. We needed the weight of the sample in the beaker to be accurate to a fraction of a gram. We successfully detached the two pieces of glass, but the weight of the beaker had certainly changed. So, we worked backwards using the MFF.

The first Latin class had a strong effect on me. Mrs. Sorenson, a somewhat elderly lady, handed out a three-page single-space text of one of Cicero’s orations. She explained that this was our assignment.

In that first session I was asked to read aloud a short section. The other students giggled at my pronunciation. They had all taken four semesters of Latin at U-M. In my eight semesters at Rockhurst High School we used the Church’s pronunciation. At U-M (and, I presume, at other heathen institutions) they used a different pronunciation in which v’s sound like w’s in English, and c’s sound like k’s. There were a few other differences as well. It took me a while to get used to this.

The three pages of translation was a lot more than I expected as an assignment. However, the first class was on Thursday, and the next class was not until the next Tuesday. I knuckled down over the weekend, and I felt pretty comfortable about being able to translate the whole speech on demand.

The next Tuesday I was not called on, and the class only got through the second paragraph on the first page. It turned out that when the teacher had said that this was our assignment, she meant the assignment for the entire semester!

So, I had a lot more free time than I had calculated.

I did very well in all four classes. I was not a bit surprised that I received four A’s. Only one other guy in Allen Rumsey matched my GPA. We both won the Branstrom Freshman Prize, which was a copy of Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations.

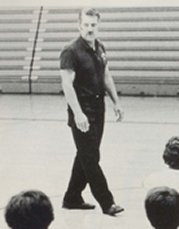

Everyone was required to take two semesters of phys ed as a freshman. I took golf during the first semester. I learned nothing. The teacher was a coach in some other sport. Most of the time we just hit golf balls into nets in the old Waterman Gymnasium, which was torn down in 1977.

One of our classes was held at a driving range well south of campus. I walked to class; it was the only time all year that I broke a sweat. We got to see our instructor hit a golf ball. He never whiffed, but he had an enormous slice. There is no way that he could break 90 with that swing, but he taught a course in golf at the best university in the state.

Debate: If you need a primer about intercollegiate debate in this era, you can find it here.

My partner, Bob Hirshon, who lived in East Quad, and I occasionally met to prepare for the Michigan Intercollegiate Speech League tournament. Since we were only scheduled to debate on the negative we did not need to coordinate our approaches too much. I researched the good things about our treaty obligations to NATO, SEATO, OAS, and the UN and prepared some disadvantages to leaving each. I think that Bob and I also talked about what we would do on the affirmative when we had to debate both sides, but I don’t remember what kind of case we decided on.

I have reason to think that the MISL tournament was held at Wayne State. U-M brought a handful of novice pairs. There were only three rounds. All three affirmative teams that we faced argued that the U.S. should pull out of NATO. I gave virtually the same constructive speech three times. It claimed that the pullout would be damaging economically, politically, and socially. None of their answers to these arguments seemed very good to me. The teams that we faced would have been considered mediocre to bad on the Missouri high school debate circuit.

The judge voted for us in all three debates, and I was was awarded more speaker points than anyone else. I don’t remember that I actually won a prize, but they might have given me a certificate or something like that.

I think that Bob was also one of the top speakers. After they had announced the second-place speaker, Bob nudged me and said, “It’s going to be you.” Having no comparable experience in high school, I was still quite surprised. The other U-M teams had mediocre records or worse.

It seems as if we must have gone to at least one other tournament during the first semester, but I have no recollection of it. I don’t even remember any practice debates, but we may have had a few.

They did send Bob and me to some exhibition debates, at least three. I remember one vividly. We went to one of the Ann Arbor high schools and debated against each other in front of an assembly. We wore our suits and told lots of jokes, and the kids loved us.

What I remember most vividly was how young and small the high school students looked. In the movies college kids come back to their old high school and seem to fit right in. In contrast, after I had spent only a month or so at college, these kids looked like grade-schoolers to me.

I eventually met most of the other people on the debate team. The top team was Lee Hess and his partner, a red-haired guy named Rosenberg or something like that. They had represented U-M last March at the district’s qualifying tournament for the National Debate Tournament. Their record was 0-8. At the time there were many good teams in the district, but I feel certain that there were also some that I would consider horrible.

Jeff Sampson worked with the varsity teams a lot. I don’t remember anyone working much with Bob and me. In early December I was therefore very surprised when Dr. Colburn asked me to meet with him, Jeff, and Lee Hess. I learned that Lee’s partner had quit the team, and they wanted me to debate varsity with Lee in the second semester. This would require me to go to quite a few top-quality tournaments, which would mean missing classes.

I was shocked that they had chosen me over all the other more experienced debaters. The most amazing aspect was that they wanted me to do second affirmative. Generally, the stronger debater does the 2A. The first affirmative constructive is actually written out ahead of time. How well it is delivered is not really considered very important by most judges. The debater just reads it. So the 1A’s only responsibility is the five-minute rebuttal. It consisted of presenting arguments rapidly, not selling them.

I also was asked to be 1N, which was fine with me. The 1NC usually presents a lot of arguments, and I could “spread” better than Lee could. His job would be to analyze the affirmative’s plan and come up with reasons why it was a bad idea. Experience pays off in that role.

I decided to give it a try. I had had so little difficulty with classes in the first semester that I had gained a great deal of confidence about classes. Also, of course, I absolutely loved going to tournaments—win, lose, or … uh, there are no draws in debate. You can go 4-4, however.

Jeff and Lee and I worked together through the end of finals. We decided to run a “squirrel” case on the affirmative—ending the commitment to be the first country to put a man on the moon. At the very least this approach would mean that more experienced teams would not be able to use most of their tried-and-true “canned” arguments against us. I was definitely up for that.

In those days debaters kept evidence—short quotes from books and magazine articles fully cited on 4″x6″ index cards.2 By the end of the year top debaters amassed thousands of them carried them in steel cases or briefcases. Walking from one classroom to another at a tournament was sometimes a real workout.

The best schools had systems for making sure that all debaters on the team had access to all the evidence recorded by al debaters on the team. Some even traded with other teams. U-M had no such system. I was fortunate to inherit the evidence amassed by Lee’s former partner.

Everyone organized his/her own evidence. Tabbed dividers were required. It seemed obvious to me that the tabs should be numbered like an outline: IA1a, etc., but not everyone did this. I don’t know how they managed. I pulled at least fifty cards per debate, and it was crucial to place them back in the right section. Also, at least twice in my career a drawer of cards fell off a desk and spilled all over the floor. It never took me more than five minutes to put the cards back in order.

In those days my handwriting was still good enough that my partner and others could read it. Later I typed all the cards.

I also purchased a large artist’s pad to use for taking notes in debates, a process called “flowing”. Most people in those days used legal pads, but I could never get an entire debate on one sheet of legal paper, and I wanted to be able to see the debate at a glance.

One advantage that U-M debaters cherished was the amazing network of libraries on the campus. If it had been published, we could almost certainly lay our hands on it.

Allen Rumsey House: For all four years I enjoyed living in Allen Rumsey House immensely. It was conveniently located, and I got along fine with almost all of the guys. It was a little difficult to get used to having only two showers and three toilets available for thirty residents, but many guys were elsewhere much of the time.

There was usually a card game going on our floor—hearts, spades, or euchre. We also played another trick-taking game called “Oh, hell.” I came up with a revised scoring method that everyone adopted. One day in the first week of class Gritty introduced me to Charlie Delos from Bloomfield, who know how to play bridge. We played pretty often against Gritty and Andy. Eventually, a more or less permanent bridge game arose in the lounge. I was a frequent but not constant participant.

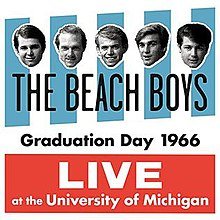

Charlie Delos had a date on October 22 for the Homecoming Concert that featured the Beach Boys. She canceled at the last minute. I bought her ticket from Charlie. The opening act was the Standells, a glorified garage band from Boston. All of their songs were forgettable except for the finale, which they called a “medley of our hit”, “Dirty Water.”

The Beach Boys recorded the concert as a live performance. They began with “Help Me, Rhonda”, which started suddenly while it appeared that they were still tuning their instruments. The highlight was “Good Vibrations”, a big hit for them that no one in the audience had ever heard before. Despite all the special effects it was just as good in person as on the record. All of the original Beach Boys (the Wilson Brothers, Al Jardine, and Mike Love) plus Bruce Johnston played and sang. It was a great day. We got to see the Wolverines beat Minnesota 49-0, and then saw a great concert. I suspect that Charlie would have preferred the date.

One of the few people who got under my skin was my roommate, Ed Agnew. He had a very strange schedule. I got up early, showered, dressed, and left by seven or so. He slept late every single morning. I never saw him in the afternoon or evening. He would roll in some time between three and four in the morning, turn on the light, and (loudly) wash his face in the sink with a lotion that he kept in a squeeze bottle. The sink was on my side of the room, and the light woke me up every time. It was very annoying.

I never saw the Ag take a shower or brush his teeth in the entire semester. Neither had anyone else on the floor. He might have taken showers at phys ed classes, but still.

The Ag spent most of his time at the undergraduate library, which everyone at Michigan calls the UGLI. There are many good places to study at Michigan. The worst is the UGLI. The selection of books is both weak and obscure. Concentration is virtually impossible because of all of the activity. In short it is primarily a pickup spot, but I never saw any evidence that the Ag had any luck in that department.

The one thing that he had going for him was his stereo. However, his taste ran to big band music. His favorite album was Victory at Sea. If he turned on the stereo in my presence, I had to leave.

Ed’s parents moved to California. He dropped out after the first semester. I knew that his grades were awful; he may have flunked out.

Charlie also did not like his roommate very much. He moved into Ed’s bed in 315 for the second semester. I liked Charlie a lot, and he even had a stereo. It was not quite as nice as Ed’s, but it would do.

The two guys across the hall, Dave Zuk and Paul Stoner became pretty good friends. Both were in the engineering school, which was easier to get into in those days than Literature, Science, and the Arts. Dave knew a lot about electricity and electronics. Paul struggled in the classes, but at least he made it to the second semester, which is more than the Ag could claim. We played a lot of hearts. Paul was a master of what we called the “Stoner Run,” in which, having already lost a heart, he would try to see how close he could come to taking all of them. He usually collected the other twelve twelve.

Stoner had a home-town honey (HTH) who was still in high school in Adrian, MI. This astounded me. I had participated in some exhibition debates in high schools. They seemed to be full of midgets! At any rate, Paul invited me to Adrian (only 20 minutes away) one weekend day. It was nothing to speak of.

In November or December Paul’s girlfriend dumped him. Paul was incredibly distressed. This was the first time I ever encountered this phenomenon.

AR had a house council that met every week on Wednesday evenings. The secretary took minutes, typed them up, mimeographed 50 copies, and slid a copy under every door. I don’t remember his name, but I really liked his style. Halfway through the semester he resigned. Gritty asked me to take his place. It seemed easy enough, and so I did it. Thus, I became embroiled in dorm politics almost as soon as I arrived.

AR had a few traditions that I was not expecting. One was the inter-floor water fights. They usually pitted the third four residents against the fourth floor. One would start with an unexpected dowsing with a water balloon or a waste basket full of water. Soon water was several inches deep in the hallways, and it became critical to dam up the bottom of the doors to the rooms with towels and whatever else was available. The most epic of these battles led to waterfalls cascading down the stairs all the way to the basement.

I am not sure when it started, but some guys on the third and fourth floors also threw water balloons. The house president, Ken Nelson, had a great arm. He could throw one from the fourth floor all the way across the street to the front door of South Quad. The hapless victims never suspected that the missile had come from such a distance.

The guys in 415, right above us, invented a water balloon launcher that defied belief. It consisted of surgical tubing that was affixed to each side of a window and to a kneepad that held the ammunition. two guy would then pull back the kneepad across the room, through the door, the hall, and into room 414, where they carefully set the kneepad down on the floor and simultaneously released it. Mishaps were common, but if they were careful, the balloon came out with absolutely incredible force. It would clear both the center and the northern section of West Quad across the street and over the trees (smaller than shown in the image) into the plaza between the LS&A building and the Administrative Building. Spotters from AR were stationed there to document the bombings. No one could ever have suspected where they came from. They called the device the “Chee ho tay”. I don’t know how they spelled it.

I personally saw them operate the device, and once I saw a balloon speed over the top of the north side of West Quad.

Nobody called me “Wave” in Ann Arbor. In Allen Rumsey house most people called me KC or Case. Elsewhere, I was just Mike.

Sports: Despite the fact that a super-talented future All-American basketball player lived a few feet to the west of Allen Rumsey House, everyone was most interested in football. All the freshmen pooled all of their ID’s together, and someone purchased a block of tickets for us in the corner of the end zone.

I remember that just a few days after school started one of the assistant football coaches visited A-R and put on a short presentation about the U-M football team. A large group of the house’s residents crammed into the rec room to watch a film that he showed about the team. It featured footage of some of the underclassmen on the 1965 team who would be playing in the first game that was just around the corner. The coach that year was Bump Elliott3, and my favorite player was Dick Vidmer4, the quarterback. By the end of the season I judged that the former did not take full advantage of the latter’s abilities.

A fairly strict ritual was followed on the Saturdays of home games. After breakfast a group of us would watch cartoons5 downstairs. Depending on the starting time for the game, we would then try to grab an early lunch before following the band for the one-mile walk to Michigan Stadium6. This would get us there in plenty of time before kickoff.

The stadium was surprisingly unimpressive from the outside. I knew that it held 100,000 people, but it did not seem possible. To me it looked smaller than Municipal Stadium in KC. When I entered the stadium, it became clear. Fully half of the stadium is below street-level. When you entered, half or more of the stadium was below you.

If the team was on the road, we would listen to Bob Ufer’s completely unbiased accounts of the action on the radio. More than a few fans brought transistor radios to the games and listened during home games, too.

Even then, Michigan Stadium was gigantic. The team was mediocre during my first two years at U-M. Nearly all undergraduate students attended the games, but the graduate students represented approximately half the student body. They and the alumni did not attend in numbers nearly as great as in 1968 and every following year.

This is not to say that there were empty seats those first two years. Michigan Stadium did not have seats. It had very hard metal benches with numbers painted on them. You sat on the number corresponding to your ticket.

An obvious problem developed if people were wider than the distance between numbers. Very heavy students were a lot less prevalent then, but for the Ohio State game with everyone in parkas in late November, a few late arrivals ended up sitting on the steps.

Very few students regularly attended basketball games, even when Rudy Tomjanovich was scoring 30+ points per game. I remember watching one game in the Crisler Center in my sophomore year. All of the fans were making fun of the way that the coach, Dave Strack, clapped his hands when the team huddled during a timeout.

Intramural sports were big in Allen Rumsey, especially volleyball and ping pong. I remember John Dalby, the fourth floor RA, started recruiting volleyball players during the first week of school. When I arrived, AR had never won the overall IM dorm championsip, but we were defending champs in volleyball.

I did not play on any of AR’s intramural teams as a freshman. In the first semester I was concerned with classes and other matters. In the second semester I was much too busy debating.

Many pickup football games were played that first semester. There were several fields that were in walking distance of AR. I made many good friends in these games.

I attended a few of the house’s intramural contests, including the two epic struggles in the finals of ping pong and volleyball, both against Wenley House. We lost in ping pong when our best player, Gritty, was defeated by a guy who overcame the handicap of a cast on one leg with reflexes of a cat. However, we won the volleyball championship by keeping the ball away from Rudy T. at all costs.

1. Among many other accomplishments, Dr. Donald J. Lewis became chairman of the U-M math department. He died in 2015. His Wikipedia page is here

2. At some point in the twenty-first century index cards and everything else on paper was replaced by laptops.

3. “George of the Jungle”, which began in 1967, was definitely our favorite. I don’t remember what, if anything, we watched in 1966.

4. After he left Michigan Bump Elliott became the Athletic Director at Iowa. He died in 2019.

5. Dick Vidmer got a bachelors, a masters, and a PhD at U-M. He studied economics as an undergrad and Soviet politics and government as a grad student. He developed multiple sclerosis in 1983, which forced him to retire in 1999. He died in 2022

6. I never heard anyone in Ann Arbor call Michigan Stadium “the Big House”.