Chapter 1: Men in Funny Hats

“Pay No Attention …”

Brilliant white starch offset the shapeless figure’s otherwise black raiment. She rose from behind her desk and glided on invisible feet across the front of the classroom. Her stark appearance and decisive mannerisms fascinated the girls. The boys fixated on her action hand, the one wielding that long stick with the hook on the end.

Something caught the eye of the mischievous red-headed kid seated by the door. He leaned out over his desk to get a better angle. Then he excitedly pointed and exclaimed, “S’ter, there’s a bunch of guys in funny hats behind your back!”

“Sit up straight, Sean,” the nun replied, “and concentrate on today’s catechism lesson – the three types of sin.”

“But, S’ter, lots of them are doing nifty tricks back there. Who are they, anyway?”

The stick smacked smartly against her other hand. “Did I make myself clear, Sean O’Malley? Pay no attention to those men behind my habit.”

* * *

Color and action, heroes and villains, gunslingers and shortstops. The world of our class’s collective imagination was peopled by the likes of Davy Crockett, Johnnie Tremain, Zorro, and Elfego Baca. We enjoyed them in black and white, but now that we had visited Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color, we were enthralled. The quotidian life of parochial school in the fifties and sixties seemed so drab by comparison. Our teacher, Sr. Mary Immaculata, looked like … well, she did not actually look like a person. She had a nose, a mouth, and two eyes, but the components did not seem to assemble into a face. Her world was as black and white as her habit. Every question had one right answer. No colors; not even shades of grey.The nuns drilled into us young Catholics precisely what we needed to assure our eternal salvation, but they curiously neglected the men who led our Church through good times and bad. Sean never actually glimpsed any popes concealed behind a nun’s habit. In fact, despite year after year of religion classes, thoughts of those old men in funny outfits seldom surfaced at all. We never asked Sister Mary Immaculata much about the popes, but what if we had?

* * *

“S’ter, S’ter! When are we going to learn about the popes?”

“Yeah, S’ter. Does the pope have super powers?”

Sister Mary Immaculata surveyed the fifty or so restless suburban kids whom she was expected to transform into devout knowledgeable Catholics. A sigh preceded her explanation: “We have already discussed the popes. St. Peter was the first one. Later popes inherited the powers granted to Peter by the Lord Himself. His Holiness is the unquestioned leader of the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church. The Holy Ghost speaks through him to provide us the knowledge and wisdom to help us become true children of God. This is the Holy Father’s special power, and it is a wonderful thing.”

“Can we become pope when we grow up, S’ter?”

“No, Sean, the pope is chosen by the Holy Ghost through the Sacred College of Cardinals. The Holy Ghost decided several centuries ago that Italians make the best popes.”

“Keen,” grinned a mop-head who could pass for Tony Bennett’s little brother. “When I graduate from the College of Car’nals and become pope, I’m gonna ex-connicate all you jerks.”

“No, Salvatore, you are an American, not an Italian. And the question period is over; it is time to review the catechism: Who made you?”

“God made me.”

“Why did God make you?”

* * *

The diocese provided the nuns with a syllabus. It ignored the popes. Officially, Church history seemed to consist of Jesus’s life, the decade or two dominated by St. Paul and the apostles, some Romans in catacombs, a very long lacuna, and today’s Church. A few saints and missionaries were tossed in. Ask any Catholic or ex-Catholic to identify three popes from before his/her own lifetime. Even nuns and priests are stumped by this simple challenge. There have been over 260[1] popes. Is it not peculiar that highly educated Catholics cannot identify even three of them? This is just wrong. What other institution has influenced western civilization as much as the papacy? Furthermore, many popes were extremely controversial in their day. People should be arguing about them in classrooms, on street corners, and in bars. Dismissing the popes as interchangeable old men should be a sign of ignorance.

What’s more, learning about the popes can be exciting. Many had exceptional talents; the first musical comedy was written by a pope! The vibrant personalities of several others became the stuff of legend. One lived alone in a filthy cave right up until his election. After a few months his eventual successor talked him into quitting, locked him up in prison, and was even posthumously tried for his murder. One pope’s wife and daughter were brutally murdered. Two popes were rowdy teenagers. Popes have been many things, but they were seldom boring.

The fact remains that presenting papal history is quite challenging. To state the obvious: there are too many leading men, and few seem heroic. The constantly changing roles played by the popes demanded much more subtlety than those of the kings and emperors who dominate the history books. Furthermore, getting the story started is very difficult; information about the first few dozen pontiffs is limited and dubious. The Church began encouraging education in the thirteenth century, but it has never emphasized its own history. Its official records have been for the most part inaccessible even to Catholic scholars.

Such reticence need not deter the curious. An abundance of provocative sources is now available to a determined researcher. The fact that many popes were much too colorful for the comfort of a Church that has generally preferred a black and white world should only make the rest of us more curious, and rightly so. How can anyone who hopes to understand western culture ignore the institution that was at its very core during its long gestation?

An interesting question arises: If Church history had been been part of our class’s syllabus, what would the nuns have told us about the popes? One thing is certain; they would have started with St. Peter.

Simon v. Simon

The Church lists the apostle formerly known as Simon as the first Bishop of Rome and therefore the first pope. He received his very name and vocation from the Lord himself. When the bad guys arrested Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane, Peter drew his sword to defend Him. Years later Peter apparently settled in Rome. Steam must have poured out of his ears when Simon Magus strutted into the city and challenged the excitable apostle to demonstrate God’s power before Emperor Nero himself. Father Henry Brann has ably related the story of this epic confrontation:

In the twelfth (year) of Nero … Simon Magus so captivated the Romans, and Nero especially, that they decreed to him divine honors. On the day that Simon Magus was to delight the Romans by an ascent in the air, and they were in most anxious expectation to see such a prodigy, St. Peter and St. Paul went to the spot where this was to take place, full of confidence in God that he would confound that imposer and undeceive the poor deluded people. And so it was: as Simon Magus, before an immense crowd of people, was already carried by the wicked spirits on high in what appeared to be a carriage drawn by fiery horses, St. Peter made a fervent prayer to God that he would abase that man, and, behold, in an instant, the fiery horses and chariot vanished away, and Simon Magus fell headlong to the ground and died.[2]

That’s what I’m talking about! The fiery chariot stunt might have wowed the yokels out in the hinterlands, but Simon Magus should have thought twice before bringing that weak stuff into the pope’s house. Making the Magster go splat in the middle of the forum was no doubt a crowd-pleaser. Still, how cool would it have been if the first pope had asked the Lord to direct the flaming chariot to swing back around to collect Peter and Emperor Nero for an aerial tour of the seven hills of Rome? That would have really put the “pop” in “pope.”

Still, even Fr. Brann’s version of Simon v. Simon would have undoubtedly sparked interest in the youngsters in Sr. Mary Immaculata’s class. However, she never told us this story, and with good reason. We were an inquisitive lot, and many of us had an all-consuming interest in super powers. We all knew that Clark Kent’s were derived from his birth on the planet Krypton. The fact that Barry Allen’s speed was the result of his being struck by lightning was likewise common knowledge. Hal Jordan received his power ring from an alien. J'onn J'onzz was himself a Martian. We could readily catalog the strengths and weaknesses of each member of the Justice League of America as well as those of their nemeses. One of us was bound to demand specifics concerning the super powers of St. Peter and Simon Magus.The nuns would naturally have attributed St. Peter’s success to the power of prayer. He was an apostle, a pope, and a saint; the Lord could be expected to listen attentively to his entreaties. Not good enough. We had all prayed for super powers, and what good did it do? No, we would want to know about Simon Magus. Where did he get that flying chariot? It wasn’t Wonder Woman’s invisible airplane, but it was much cooler than any earth-bound vehicle invented before the Corvette. Who were those “wicked spirits” who made it fly? How did they do it? Are they still around? These lines of inquiry might have drawn Sister Mary Immaculata off of her turf, the catechism, and onto ours, maniacal speculation about fictitious worlds. She was probably wise not to bring it up.

St. Peter’s pontificate was a difficult act to follow.[3] Spell-binding stories about St. Linus, the second pope, are non-existent. According to the Vatican’s Annuario Pontificio a native Roman named Cletus served as the third Bishop of Rome between 78 and 90. Next came the decade-long pontificate of Pope Clement I, most likely a Jew. The fifth name on the Vatican’s list was Anacletus, an Athenian whose term ran from 100-112. His major accomplishment was to designate a papal burial place in the Vatican right beside St. Peter’s own sepulcher.

Examining the family resemblances of related popes can be fun. Line drawings of even the earliest popes have been published, and from the Renaissance to the present day elegant portraits of the pontiffs are easily located. Popes in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were often related to previous pontiffs, but the first familial relationship dates back to the first century. Pope (and saint) Anacletus was from the same family as Pope (and saint) Cletus. To my eye Anacletus appears to sport bushier sideburns than Cletus’s, and the look in his eye seems slightly mischievous.[4] Both obviously inherited the familial Greco-Roman nose.Recent scholarship has revealed that these two pontiffs had a closer relationship than Eng and Chang. Annuario Pontificio is periodically updated by the Vatican. The 1947 edition for the first time removed Anacletus from the official list for the stunning reason that he and Cletus evidently[5] shared the same body. Cletus was a nickname for Anacletus. A.P. also changed the dates of his papacy to span from 76 to 88. The New York Times and a few other journals reported this change, but the story generated little traction. If Sr. Mary Immaculata had mentioned it, we might have bombarded her with questions like:

• How could Pope Cletus/Anacletus (he is also sometimes called Anencletus) be born in both Rome and Athens? Would that not be painful for his mother?• Was this a Bruce Wayne and Batman thing, a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde thing, or just a horrendous blunder by papal historians?

• Who validated Anacletus’s sainthood? No one expects every saint to possess Peter’s ability to obliterate airborne chariots with invisible surface-to-air missiles. On the other hand, surely physical existence must be a prerequisite for sainthood. The Devil’s Advocate in this case must have mixed up his meds.

• What about the 1,800 plus years of prayers directed to St. Anacletus? Did they just get lost in the ether, or was call-forwarding used to transfer them to St. Cletus?

• How could the dates be so far off? Cletus had been dead for twenty-four years when Anacletus supposedly expired in 112. Did no one notice his absence during all of that time? This would be like a modern historian recording an imaginary President Anakennedy on the scene into the late eighties.

The Fourth Notch

Only a few months after he had assumed the papal pallium and tiara, Callixtus arranged to meet with Elagabalus, the young man who had just been designated Roman emperor. The Holy Father had been dreading this interview. Third-century emperors were still clueless pagans with scant appreciation of Christianity. This teenager Elagabalus promised to be a particularly difficult case. He already spoke of replacing the traditional pagan gods and goddesses with a new set of his own devising. As a former priest of a Syrian god, he may even name himself a divinity; other emperors had entertained such ludicrous notions. The pope intended to demonstrate how a strong working relationship with the Christian community could advance the goals of both Rome and its emperor. At the very least he must gently steer Elagabalus away from any notion of persecuting the followers of Jesus.

For the occasion Pope Callixtus donned the simple green vestments of the summer season. Only his bishop’s miter covered his head; the tiara he left behind in the Vatican. Although he addressed the emperor as a religious leader, not a fellow potentate, nothing precluded stylish transportation. As Callixtus braced himself beside the driver of the pontifical chariot, he admired the muscles rippling on the backs of the matching white stallions before him. A moment later they rumbled through the cobbled avenues of the Eternal City at full gallop.

No warrior was he, but neither was the pope defenseless. He bore his staff, of course, the crosier identifying him as the shepherd of the Christian flock. Concealed beneath his vestments was the sword of St. Peter. Forged nearly two centuries earlier, it still could serve as a formidable weapon. The pontiff fingered the three notches on its hilt. One, he presumed, was for Malchus’s ear,[7] but what of the other two? Obscured by the mist of papal history were the ineffable fates averted by some previous pope’s wielding. Callixtus was a peaceful man; he sincerely hoped that it would not fall on him to draw the sword – not now, not ever.He need not have fretted; the audience went quite well. Had his faith been a trace stronger, he might have foreseen as much. When the cardinals had first seated him on Peter’s throne, Callixtus had felt the Holy Spirit course through him, the same force that he had often witnessed in Pope Zephyrinus. That great man had an unmistakably saintly aura, a visible glow, yes, a halo.

At the sound of Pope Callixtus’s first utterances, the juvenile emperor’s jaw dropped, and his eyes bulged with wonder. Even before the pope had finished, Elagabalus humbly prostrated himself before the pontiff and kissed his foot. The young emperor never converted to the true faith, but in his entire reign he never threatened the Christian community.

The threat came from another quarter entirely.

It all started on a sunny Wednesday a few weeks after the pontiff’s assignation with the emperor. His Holiness immersed himself in an important task.

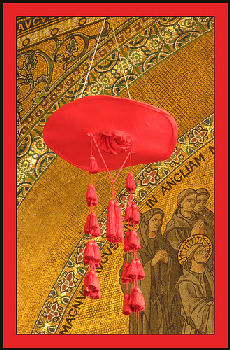

The Christian missions in Africa had experienced rapid growth. Pope Callixtus understood that he must appoint the most gifted bishops available to provide these fledgling Christian communities with first-class leadership. He pondered the list of names furnished by the curia. This one would probably be fine; that one was too ambitious; a third he could not spare. Only two positions remained unfilled when Cardinal Benvenga rushed in. As he rounded the corner, the galero slid off his tonsured pate and pinwheeled across the polished marble floor. Anyone could read the distress on his features. “Your Holiness, he’s done it. I swear that it is true. Father Hippolytus has gotten himself elected by a disgruntled group of the clergy. He is openly wearing both the tiara and the pallium. He has declared himself … the antipope!”

“Calm yourself a moment, Eminence,” replied Pope Callixtus. “Where is Hippolytus now?”

“He’s, he’s in St. Peter’s Square, Your Holiness,” the scarlet-robed prelate stammered breathlessly. “He has called you out. He claims that you are unworthy of the papacy, and that you are not the legitimate successor to St. Peter.”

Callixtus sighed. “His first statement is absolutely correct, of course, but the second cannot be left unchallenged. Putting our faith in the Paraclete, let us forthwith confront the upstart.”

The rebellious priest had taken his stand in the middle of the piazza. Arrayed behind him stood a grim semicircle of five priests in audacious support of this open defiance. Behind them gawked an unusually apprehensive assemblage of the faithful. Hippolytus gripped his staff with both hands as he squinted toward the pope’s apartments and patiently awaited the pontiff’s response to his challenge. His wait was short.

A gasp greeted the appearance of Pope Callixtus, clothed as usual in brilliant white, a sharp contrast to the dingy tunic of his adversary. “Cease, Hippolytus,” he commanded as he descended the steps of the basilica. “You have made your mark as a brilliant theologian. Don’t ruin it all with such a pointless gesture.”

“Says you,” was the best reply that Hippolytus could muster. He was so taken aback by the pope’s saintly aura that his famously glib tongue failed him.

The pontiff calmly withdrew St. Peter’s sword from his vestments. He cast it skyward in a seemingly random arc. In mid-air the sword separated from its sheath. A beam of sunlight caught the blade in the middle of its lazy cartwheel, and then – what? the wind? – something dramatically diverted its course toward the rebel, and a moment later Hippolytus’s right ear lay in the dirt. The antipope screamed in panic and grabbed his head to stanch the bleeding.

Pope Callixtus I calmly bent over and retrieved the severed organ. He tenderly placed it back on the head of the trembling priest. The Holy Father then invoked a silent benediction over his adversary. He proceeded to recover the holy sword, cleanse the blood from its blade, and return it to its sheath. As he did, he noticed a fourth notch on the hilt. A wry smile played about the pontifical lips.

“Forgive me, Holiness.” The tug that the Holy Father felt at his feet was Hippolytus, vainglorious no more. On his hands and knees he planted a humble kiss on the jeweled cross sewn on the pope’s scarlet slipper. And lo, Callixtus felt certain that he detected the faint trace of a halo around the erstwhile antipope’s tonsured head. As Sr. Mary Immaculata often reminded us, the Lord works in mysterious ways.

* * *

Well, OK, maybe not that mysterious. Little or no reliable[8] evidence verifies this Disneyfied account of events. Furthermore, a few anachronisms slipped into the manuscript.

• There was no conclave after Pope Zephyrinus’s death. Information about how the popes of the first few centuries were chosen is very sketchy. Rules for papal succession were not formalized until 1059! The College of Cardinals did not exist in 217; in fact, there were no cardinals in the third century.

• Pope Callixtus I and Elagabalus were contemporaries, but no one recorded that they met. The kid was crowned in Syria and did not come to Rome until more than a year had elapsed. At any rate, consulting with Elagabalus would have accomplished little; in 217 the real powers in the empire were all women.

• Pope Callixtus might have worn a pallium and a miter, but the first papal tiara was not fashioned until many centuries later.

• The custom of kissing the pope’s feet was introduced – at the earliest – in the pontificate of Pope Leo the Great in the middle of the fifth century.• Callixtus certainly never lived in the Vatican; the first papal residence there was built in the fifth century, and the pope usually stayed elsewhere until 1870.

• As far as anyone knows, St. Peter’s sword saw no action whatever after that mishap in the Garden of Gethsemane.

• The Church in Africa was vibrant, but the popes had no say regarding appointments of bishops there.

• The galero, that enormous flat red sombrero with tassels and a chin strap, was not awarded to cardinals until 1245. It has always been ceremonial and seldom worn by anyone in centuries. Even Duncan Renaldo would look ridiculous in a galero.• Tonsures were unknown before the seventh century.

• No contemporary called Hippolytus an antipope. In fact, the title “pope” was first claimed by the Patriarch of Alexandria later in the third century and was never applied to the Bishop of Rome until more than two centuries after that.

• The pope did not begin wearing white until the 1560’s.

In short, the preceding story of Hippolytus, the first antipope, and the two popes, Zephyrinus and Callixtus I, is a fabrication. Do not despair! Reality often exceeds imagination. The sole surviving first-hand account features no galloping steeds, no prostrate emperor, no comical cardinal sidekick, no duel in Piazza San Pietro, no magic sword, no miracle cure, and no haloes, but the details are equally astounding.

Is the Pope Catholic?

The Roman priest Hippolytus was reportedly a student of St. Ireneus, the Bishop of Lyons.[9] Hippolytus wrote extensively in Greek. A fair amount of his writing has survived, including his invective against Pope Zephyrinus for failing to condemn modalism, a position finally declared heretical by a Roman synod forty years after the pontiff’s death.[10]Hippolytus attributed Zephyrinus’s lackadaisical attitude to the insidious influence of the deacon Callixtus. Hippolytus had no use for this

… man cunning in wickedness, and subtle where deceit was concerned, who was impelled by restless ambition to mount the episcopal throne. Now this man molded to his purpose Zephyrinus, an ignorant and illiterate individual, and one unskilled in ecclesiastical definitions. And inasmuch as Zephyrinus was accessible to bribes, and covetous, Callixtus, by luring him through presents, and by illicit demands, was able to seduce him into whatever course of action he pleased.[11]

Hippolytus then recounted Callixtus’s sordid background:

Callixtus happened to be a domestic of one Carpophorus, a man of the faith belonging to the household of Caesar. To this Callixtus, as being of the faith, Carpophorus committed no inconsiderable amount of money, and directed him to bring in profitable returns from the banking business. And he, receiving the money, tried a bank in what is called the Piscina Publica. And in process of time were entrusted to him not a few deposits by widows and brethren, under the ostensive cause of lodging their money with Carpophorus. Callixtus, however, made away with all, and became involved in pecuniary difficulties.

Hippolytus claimed that after Callixtus squandered the funds entrusted to him by his master’s clients, he dashed down to the harbor at Porto and took refuge on a ship. Before the vessel set sail, however, Carpophorus got wind of the planned escape. Callixtus spotted his boss boarding the ship and in desperation dove into the water. The sailors hauled the fugitive out and bound him over to his master, who promptly incarcerated him. Creditors of Callixtus prevailed upon Carpophorus to release him, not from mercy but simply to deny Callixtus an excuse for failing to repay their deposits.

Callixtus, destitute and desperate, concocted a remarkable scheme for ending it all. He reportedly set out to disrupt the services at a nearby Jewish synagogue in a manner so obnoxious that the irate worshipers would kill him. Unfortunately Hippolytus did not describe the means that Callixtus employed. Did he play his collection of Yoko Ono records [12] at high volume, or did he just dress as a skinhead, deny the holocaust, and shout anti-Semitic epithets? In any case the Jews almost accommodated Callixtus’s death wish. They beat the tar out of him and then hauled what was left of him before a Roman magistrate. Even Carpophorus testified against his servant and fellow Christian. The judge flogged Callixtus and sentenced him to work in the mines in Sardinia, the Roman equivalent of the Siberian gulag.Callixtus effected his escape from Sardinia by attaching himself to a rescue mission formed by Pope[13] Victor I. Hippolytus’s text insisted that Callixtus was not on the list of the righteous whom Victor had ordered liberated, but he pleaded, cried, made a scene, and eventually cajoled his way into the select group. Victor was furious to discover this lowlife among the saintly faithful. He banished him to Antium, which is where Callixtus hooked up with Zephyrinus, his ticket back to respectability. Callixtus became a deacon, and Pope Z eventually put him in charge of the Roman cemetery that still bears his name.When Zephyrinus died in 222, Callixtus was somehow chosen as Bishop of Rome. Tolerating an illiterate pope open to bribery had been excruciating for Hippolytus, but the prospect of a miscreant like Callixtus on St. Peter’s throne was more than he could bear. Hippolytus was an unrelenting hard-liner with zero tolerance for heresy and sin. That Callixtus condoned repentant rapists, murderers, and other ne’er-do-wells receiving communion outraged him. A group of priests who supported Hippolytus held an election almost immediately after Callixtus’s. It resulted in Hippolytus being chosen as Bishop of Rome.

Hippolytus openly challenged Callixtus and his successors for eighteen long years, and he had a loyal following. During that period three different official Bishops of Rome were elected by the rest of the clergy and/or the laity. How could the papacy have brooked this competition for such a long time? Perhaps Hippolytus and his followers were deemed such laughable eggheads that they posed no threat to Callixtus and subsequent pontiffs. Since Hippolytus wrote in Greek, his arguments may have been over the heads of Roman Christians.[14] Nothing indicates that the conflict ever went beyond a battle of ideas.

According to Hippolytus, Zephyrinus was illiterate, and his successor Callixtus was a former servant, embezzler, and prisoner in a forced labor camp. No one has cataloged the tricks they employed to stay in power, but between them the ignorant Zephyrinus and the man with the checkered past, Callixtus I, held sway in the Holy See for almost a quarter century. In 235 the tale took an unexpected turn. Emperor Maximus Thrax exiled both Hippolytus and Pope Pontian (sometimes called Pontianus) to Sardinia. Legend has it that Hippolytus recanted, returned to Rome, and was martyred. The details are suspicious, but just about everyone agrees that, martyr or not, Hippolytus was probably the most eloquent theologian of the early Church. The Church finally endorsed his position against modalism twenty-seven years after his banishment. By then Popes Callixtus I, Urban I, Pontian, Anterus, Fabian, Cornelius, Lucius I, Stephen I, and Sixtus II had come and gone.Useful insights about the early popes can be gleaned from Hippolytus’s account:

• The lack of verifiable data about the early popes often has forced historians to extrapolate from scraps of dubious value. In this case, the only record is one man’s account, and by his own admission he had an axe to grind.

• Not all popes were single-mindedly devoted to ecclesiastical issues. They acted more like ordinary men with familiar human shortcomings.

• Almost everything familiar about the papacy – the papal residences, the conclave, the curia, the cardinals, the mode of dress, and even the titles – were absent in the first few centuries.

• To say that the Christian doctrine took shape very slowly understates the case. Progress was glacial. The kids in Sr. Mary Immaculata’s class labored under the erroneous impression that the catechism that we were forced to memorize had been around forever.

• In the periods when Christians were not persecuted by imperial Rome; they interacted with the other communities.

The early Roman bishops probably exerted little or no influence over other Christian congregations. About half the time the entire Roman Church was forced underground. Christianity was tolerated during the times of Zephyrinus and Callixtus I, but the epilog of their story proves that Rome’s bishop had a decidedly dangerous job. In the fifth year of his pontificate Pope Callixtus met his demise at the hands of a lynch mob in Trastevere, the Roman neighborhood on the wrong side of the Tiber River. Within a few decades the situation facing the leader of the Roman Christians had turned even more perilous. In fact, precisely this danger precipitated the papacy’s second electoral crisis.Traitors?

“Turn me loose; turn me loose, I say.”

Pope Fabian, whose portraits are disappointingly pompadour-free, was arrested in 250. He was treated brutally in prison and eventually perished there. For more than a year thereafter Roman Christians considered it too dangerous even to elect a successor; there was no pope at all. In the interim Novatian, a well-known local priest, administered the Roman Church. When elections were finally conducted, he probably expected to be named Bishop of Rome. He must have been bitterly disappointed when Cornelius, a much more laid-back priest, got the nod.

The most controversial issue of the day was not so much the ongoing Decian persecutions themselves as how to treat the Christians who had escaped them by cooperating with the emperor’s men. Two indicators of complicity were active participation in pagan ceremonies and the act of turning over copies of scriptures to the authorities. Performers of the latter were called traditores or traitors. The Latin word means “one who hands over.”

Novatian anticipated Pope Cornelius’s lenient treatment of the so-called traitors. The pontiff permitted the penitent ones to return to the Church as full-fledged communicants. Novatian insisted on a more rigid approach. He persuaded three bishops of southern Italy to elect him Bishop of Rome, thus making him the second antipope.Novatian was as renowned a scholar as Hippolytus. His were the first theological treatises written in Latin. He might have been the most brilliant theologian of his day, but he evidently lacked political savvy. Pope Cornelius, for his part, won no awards as an administrator,[15] and he was no match for Novation when it came to theological disputation. However, he proved quite adept at securing the allegiance of his fellow bishops, many of whom could not countenance excommunicating Christians for acts committed under threat of torture and death. In Rome Cornelius gathered approximately sixty bishops to back him, and he received supportive letters from many unable to make the trip.

A synod in Rome excommunicated Novatian in 251, but it by no means ended his influence. He headed the sect known as the Novatianists until 258, during which time Cornelius, Lucius I, Stephen I, and Sixtus II were officially Bishops of Rome. Novatian was reportedly martyred in 258. No one succeeded him in the role of antipope, but the ideas of Novatianism continued to spread, and the sect remained a thorn in the Church’s side for decades.

Almost from the beginning political skill seemed a prerequisite for a successful papacy. Pope Cornelius exhibited enough to circumscribe Novatian’s influence, but he was less adroit in Roman politics. The emperor banished him to the port town of Civitavecchia after he had served as Bishop of Rome for only a couple of years, and he died shortly thereafter.

Jesus had ordered Christians to render to Caesar the things that were Caesar’s. The popes of the second and third centuries needed to take this commandment literally. The Catholic Encyclopedia estimated that “Of the 249 years from the first persecution under Nero (64) to the year 313 … it is calculated that the Christians suffered persecution about 129 years and enjoyed a certain degree of toleration about 120 years.”[16] During the bad years the pontiffs must have thought of little but the Church’s survival.

St. Marcellinus’s eight-year pontificate began in 296 during the reign of the emperor Diocletian and the “Augustus” and two “Caesars” with whom he shared his authority. No reliable details of Marcellinus’s death survive, but he is nowhere listed as a martyr. Some accused the pope himself of both handing over sacred texts to the pagans and participating in pagan ceremonies. His defenders dispute those charges. Liber Pontificalis, the semi-official history of the papacy, written in the sixth century or later, labeled the pope a “traitor,” but it also claimed that he repented and became a martyr. Liber’s authorship is uncertain, and support for its claim of his martyrdom is lacking.If the circumstances of his life are so questionable, how could Pope Marcellinus possibly be considered a saint? Actually, St. Peter and his first thirty-four papal successors are all venerated as saints in the Catholic Church even though little is known about most of them.[17] We have only a sketchy idea of when each early pope held office. The surviving lists even differ over the names of the first few pontiffs and the order in which they served. The destruction of the Roman episcopal archives during the Diocletian persecution helps explain why so little information about the popes of the first few centuries has survived.

The term “saint” was seldom even used in the early Church. Instead lists of deceased holy people called “martyrs” were compiled. Their names were read aloud in some Christian services. The provenance of these martyrologies is hazy at best. Whether some names on the lists correspond to real people has even been questioned. Nevertheless, everyone on the lists, including each of those early popes, is now venerated as a saint by Rome.

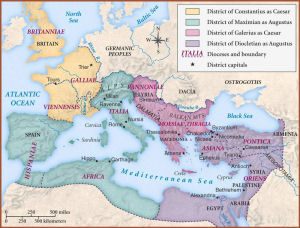

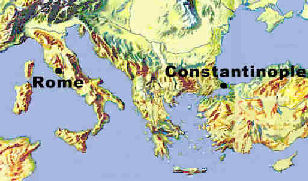

The early fourth century was so dangerous that after Marcellinus died in 304, the papacy remained vacant for four years. Sr. Mary Immaculata often describe the papacy as an “unbroken chain.” Its largest gap is the period after Marcellinus’s pontificate.By the fourth century all roads no longer led to Rome. During the “First Tetrarchy,” the period from 285-305, imperial residences were established at Trier, Thessalonica, Nicomedia, and Milan, which became the real imperial capital in 286. Rome had been demoted to a secondary status. Plagues, floods, and other disasters had also beset the Eternal City. The combination of factors caused both the total population and the influence of Rome to shrink drastically from St. Peter’s day to Marcellinus’s.

The Sign of Constantine

Constantine succeeded the tetrarchs in 312 by vanquishing his rival and brother-in-law, Maxentius, at the Milvian Bridge. The victory came after Constantine reportedly beheld an image of the cross – or perhaps the Greek letters chi and rho (the first two letters of Christos) or maybe just an array of stars – with the phrase “In this sign you will conquer.”[18] The event impelled Constantine to embrace Christianity’s symbols. He reportedly began displaying them in battle, and he attributed his success to Christ’s intervention.The next year Constantine and Licinius issued the Edict of Milan, which ended the persecution of Christians and promoted freedom of worship. By 324 Constantine had consolidated his power and crushed all who opposed the edict. The emperor never embraced Christianity to the extent that his mother, St. Helena, did, but he certainly supported it.

By the second quarter of the fourth century Roman Christians could emerge from their catacombs as the apple of the emperor’s eye. However, there was a down side. At precisely this time Constantine laid out the perimeter of his new capital, and he located it far from Italy. So, just as the Roman emperor afforded a place of prominence to Christianity, he pulled up stakes and moved the imperial headquarters to Turkey.It was no shock that Constantine selected Constantinople as the name for his capital. The emperor’s father was named Constantius. He had a half-sister named Constantia. His first son, who had somehow attained the name Crispus, he executed for adultery. The sons whom he allowed to live were named Constantine II[19], Constantius II, and Constans. He named his daughter Constantina. I never discovered his dog’s name, but I will lay the usual eight-to-five odds that I can guess its first seven letters.

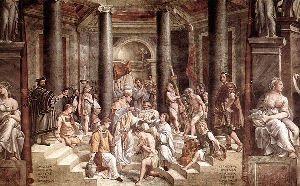

Until his death in 337 Constantine was the best friend that the Church had ever had. From his new headquarters 853 miles away, he showered the Roman Church with imperial funding. His generosity provided the wherewithal for the Basilica of St. John Lateran as well as the first Basilica of St. Peter on Vatican Hill. Constantine insisted that all Christians embrace the same beliefs, an ambitious project that required designation of an official set of books of the Bible and formulation and promulgation of a comprehensive creed. This quest for coherent dogma was unusual for religions of this era. Few even possessed written sources. Many sects considered doctrine less important than the manner in which ceremonies were performed. Worshipers feared that procedural errors, the wrong type of sacrifice, or poor timing might incur divine wrath.Christianity boasted a rich literature, in fact a bit too rich. Orthodoxy was no more prevalent than when St. Ireneus had railed against the heresies 150 years earlier. Bishops championed fundamentally different interpretations of basic theological concepts. And where was the pope? In the century and a half since Ireneus articulated the problem, no Bishop of Rome seemed to expend much energy developing or promoting a standard scripture or creed. Indeed, pontifical attention often focused elsewhere. Pope Victor I, for example, was a tiger when it came to encouraging all Christians to celebrate Easter on the day calculated by a certain astrological formula. Sr. Mary Immaculata would never be so judgmental. Many early popes deduced from the gospels that the second coming of Christ was imminent; they strove to prepare the faithful for that momentous event. Moreover, insuring the very survival of the Christian community may have left little time for doctrinal niceties.

Constantine was an emperor, not a bishop. Unlike both Ireneus and the popes, he had the resources to do something about the problem. What he did was convene a council.

Popes, Councils, and Heresies

Councils[20] are big conventions attended by bishops. Other important people often participate. There is little discernable regularity as to the when, where, and why of councils. The popes called some councils; at times others convened them. A few have been triggered by previous councils. Some included all of Christendom; regional councils were also common. Scripture provides some precedence for councils; the apostles apparently gathered together several times to make decisions as a group. The complex relationships between popes and councils evolved over the centuries.

A common theme of early councils was addressing various heresies. You are a heretic if your belief contradicts mine. However, if there is no agreed-upon basis for the determination of the truth, it might be difficult for me to convince a third party of your heresy. In fact, you might well advance the deluded claim that my position is heretical. Resolving such a controversy requires two steps: 1) establishing an agreed-upon foundation of belief in writing, i.e., “scripture”[21]; and 2) prescribing the orthodox interpretation of the scripture.

Twenty-seven books comprise the current New Testament. In the first three centuries many additional works served as the bases for Christian liturgical services. With so much material available, Christians in the first few centuries could believe almost anything. Even though Sr. Mary Immaculata might conclude that things were not much better today, modern Christians agree on all, or at least nearly all, of the books of the New Testament. For centuries no such consensus existed. In the 180’s Ireneus listed twenty approved books in his Against Heresies. Eusebius in the fourth century more or less accepted Ireneus’s list. The Bishop of Alexandria, Athanasius, put together the definitive list of twenty-seven books in a letter written in 367. The same collection had been approved in 363 by the regional Council of Hippo and then by the Council of Carthage in 397. Thereafter the controversy subsided.This merits mentioning for two reasons. In the first place how could the Church need more than three hundred years to address such a fundamental problem? Sr. Mary Immaculata always insisted that God’s Word as illuminated in Holy Scripture had been invariant since day one.

The second anomaly was that the composition of the New Testament was settled by an Egyptian bishop and two African councils. Did Athanasius really think that as Bishop of Alexandria he had the authority to rule on this matter? Did it take a council to decide the composition of the Bible itself? Why a regional council and not a council of all the bishops? Why not the Bishop of Rome? And most of all, why did no pope rule on this earlier?

These are difficult questions. In the early centuries the absolute authority of the Bishop of Rome was evidently not universally recognized. In fact, the eastern half of the empire never quite surrendered to Rome’s judgments. The Roman bishops often pressed for recognition of their supreme authority, but they were sometimes reluctant to exercise it in doctrinal matters. Other bishops occasionally took matters into their own hands.

The first “ecumenical” council was called not by the pope but by Emperor Constantine.[22] It was held in 325 in Nicea, in northern Asiatic Turkey. Constantine himself presided over the first session and delivered the opening address. One primary goal was to settle the dispute between Arius, a priest in Alexandria, and Athanasius, secretary to Alexander, the Bishop of Alexandria. Arius claimed that Jesus was a “creature” and therefore subordinate to God the Father, a position labeled the “Arian heresy.” Athanasius championed the orthodox concept of the Trinity. In 318 a council convened by Bishop Alexander had condemned Arius’s ideas and excommunicated him. Over three hundred bishops attended the council in Nicea. Pope Sylvester I remained in Rome while the attending bishops determined the essence of Christianity. Was something else more important? Pope Sylvester was reputedly an ultrà for his beloved Lazio soccer squad. However, most historians discredit the explanation that he refused to give up his tickets for the “derby” that Sunday with archrival Roma.After the opening session either Eustasius of Antioch or Alexander of Alexandria presided over the council. The pope condescended to send two representatives, and they signed off on the famous creed that resulted. They were not even the first signatories; that honor went to Hosius, Bishop of Cordoba. In all, 318 bishops signed the document repudiating Arianism and affirming the Nicene Creed that incorporated Athanasius’s ideas. The two bishops who refused were summarily declared heretics.Because Nicea has been officially designated an “ecumenical council,” its proclamations bind all Catholics and Christians of many other denominations. The council in Alexandria was not an ecumenical council. Its excommunication of Arius was a legitimate diocesan matter, but the council had no authority to declare his teachings heretical. Of course, these distinctions were not established until centuries later.

The Church teaches that an ecumenical council must meet three criteria:

1. It must be open to the whole world; it cannot be regional.

2. It must be presided over by the pope or his legates.

3. Its decrees must be confirmed by the pope. In some ways councils are therefore reminiscent of the regular gatherings around the kitchen table of American families of the 1950’s. All the kids cast a ballot on every topic brought up for discussion, but even when the youngsters voted unanimously that the family should deplete its savings for a vacation at Disneyland or Atlantic City, mom and dad could still enforce their choice of visiting relatives in Des Moines. The Church claims that the bishops faced an analogous arrangement. Did Emperor Constantine and the bishops in attendance at Nicea think of themselves as an advisory committee to the absent Bishop Sylvester? It hardly seems credible.

The Roman Church has unequivocally designated Nicea as ecumenical. However, since only a few bishops from the west made the long journey, the first criterion seems shaky. It is hard to see how it met the second stipulation either, but, since Pope Sylvester I definitely approved the results, evidently the third criterion trumped the others.

Popes actually enjoy a line-item veto; the pontiff can approve some, none, or all of the dictates of the bishops in council! Why then have the bishops bothered to stage these councils over and over? A few explanations come to mind:

1. The idea of a papal veto was unfamiliar when councils became popular. In 318 the highest recognized rank in the Church’s hierarchy was “patriarch.” The Bishop of Rome was only one of four, soon to be five, recognized “patriarchs” of the Church.

2. Christians – especially in the east – were more impressed by dictates of a gathering of bishops than unilateral proclamations of the Bishop of Rome.

3. The bishops appreciated the opportunity for networking.

The Unbaptized Apostle

Emperor Constantine thought of himself as the thirteenth[23] apostle. He never considered himself subservient to the Bishop of Rome or anyone else. Early in his reign a dispute concerning the Bishop of Carthage was submitted directly to Constantine. He ordered (!) Pope Miltiades to collaborate in an inquiry with three bishops of the heretical Donatist (very similar to the Novatianist) cult from Gaul. He commanded the pope to report back to him. Instead, Miltiades tried to coax the three bishops into adopting orthodox views. They again appealed to Constantine. He summoned a council at Arles headed by the Bishops of Syracuse and Arles. Miltiades’s successor, the aforementioned Pope Sylvester, did not attend this council either. The bishops failed to defer to the pope in the matter, but they did request that Sylvester promulgate their twenty-two canons, including the condemnation of the Donatists.

So, the one truly great Christian emperor, a man deemed a saint by the Greek Orthodox Church, shunned baptism, the only recognized way to avoid eternal damnation, until the very end. He was finally baptized by the most notorious Arian heretic, a man who had devoted decades of his life to pulling political strings inside and outside of the Church in order to overturn the Nicene Creed and facilitate the rehabilitation of his great friend, Arius himself.

Boring?

So what were St. Peter and the other thirty-one men who served as Bishops of Rome through the end of Constantine’s reign really like? The fragmentary information about them gives tantalizing glimpses, but little of substance. They were all saints in the eyes of the Church. Many must have performed amazing tricks to safeguard their followers from so many imperial pogroms, but, alas, specifics are in short supply. One conclusion that can confidently be drawn is that virtually nothing that most people associate with the papacy was familiar to them. They did not dress like popes, and, from what we know, most did not act like popes.

After Constantine’s time, everything changed. With the persecutions ended, the popes could address other challenges. Before we begin the papacy’s second chapter, let’s put on a Beach Boys tune:

“Bar bar bar …”

[1] Benedict XVI is #265 on the official list, but he is only the 263rd pope. This discrepancy is explained in Chapter 5.

[2] Rev. Henry A. Brann, D. D., The Glories of the Catholic Church, John Duffy, New York, 1895, Vol. I, p. 244.

[3] The historical evidence concerning the first few popes is discussed more seriously in Appendix 1.

[4] See, for example, http://www.tuttipapi.it/01_DALLEORIGINIACOSTANTINO.htm, which contains links to short illustrated biographies (in Italian) of both Cletus and Anacletus.

[5] A recent papal history still claims that they were different people! Charles A. Coulombe, Vicars of Christ, a History of the Popes, Kingston Publishing Corporation, New York, 2003, pp. 20-21.

[6] Counting St. Peter but not St. Anacletus.

[7] John 18:10.

[8] Or even unreliable, for that matter.

[9] St. Ireneus was an extremely important figure in early Church history. His most famous work listed the first twelve bishops of Rome. It also provided the first (incomplete) list of the books of the New Testament. Appendix 1 provides a more detailed account of this subject.

[10] Modalists identified God as one entity who appeared in three modalities: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This contradicted the fundamental Christian doctrine of the Trinity, which affirms that God has always existed as three persons simultaneously. If this seems like hair-splitting, you should be warned that there is more to come in the rest of this chapter and the next couple. On the plus side, once Church dogma stabilized, the hairs stay pretty much intact until Chapter 23.

[11] Hippolytus's text is taken from The Ante-Nicene Fathers: Translations of the Writings of the Fathers, edited by the Rev. Alexander Roberts, D.D., and James Donaldson LL.D., New York, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1903, Vol. V, pp. 128-130.

[12] They could not have been CD’s, because James Russell did not invent the compact disk until 1965.

[13] Hippolytus merely called him a bishop.

[14] Ironically, Hippolytus was the first to use the word “catholic.” He was referring to himself and his followers, not the Church headed by the pope.

[15] He did report that there were fifty-two exorcists plying their trade in the Roman Church. Evidently Pope Fabian had been responsible for establishing the exorcists as a distinct order.

[16] The Catholic Encyclopedia: an international work of reference on the constitution, doctrine, discipline, and history of the Catholic Church, The Encyclopedia Press, Inc., 1910, Vol. IX, p. 738. The entire work is online at www.newadvent.org/cathen/.

[17] Appendix 1 delves into the issue of the identification of the popes and the extant historical record.

[18] The Latin phrase “In hoc signo vinces” was also the bizarre motto of Pall Mall cigarettes, despite the fact that the legend has always insisted that the words in the sky were Greek: “Εν τούτω νίκα”. Another version has Constantine hearing a voice speak the phrase.

[19] George Foreman has five sons. They are all named George.

[20] The word “synod” is a Greek term that means essentially the same thing as the Latin term “council.” However, the really important episcopal meetings usually seem to be called councils.

[21] The Catholic Church recognizes a second source, “Divine Tradition,” as specified by the “living magisterium.” Most Protestant churches do not. The Catholic Encyclopedia, op. cit., Vol. XV, pp. 6-7.

[22] Who had not even been baptized at the time!

[23] Why not the fourteenth or fifteenth? There were originally twelve. Matthias was elected to replace Judas. Most Christians also consider Paul to have somehow risen to the level of apostle.

[24] The historian known as Eusebius of Caesarea wrote the historical documents cited earlier in this chapter and extensively in Appendix 1. He also authored a famous biography of Constantine. After the council of Nicea Eusebius of Nicomedia tried to walk a fine line between the Arians and the orthodox Christians, but he ended up as a leader of the Arian restoration movement.

| |

| |

Bankable Bar Bets

$ The first prelate called “pope” was actually the Patriarch of Alexandria.

$ The first thirty-five popes are all considered saints.

$ For many centuries an imaginary Greek pope named Anacletus was included in the official list of popes. “Anacletus” now is deemed to have actually been the same person as St. Cletus, the third pope, who may or may not have been Greek.

$ Pope Zephyrinus was reportedly illiterate.

$ The word “catholic” was first used by an antipope in reference to his own followers.

$ Before he became pope, Callixtus I reportedly tried to commit suicide by loudly disrupting a Jewish religious service.

$ Pope Callixtus was convicted of embezzlement as a young man, flogged, and exiled to the mines.

$ The first antipope, Hippolytus, was “in office” for eighteen years.

$ The first antipope is a canonized saint.

$ The papacy was vacant from 258-260 and then again from 304-308.

$ The first ecumenical council was called not by a pope but by Emperor Constantine.

$ The authoritative list of the books of the Bible was compiled not by the pope but by an Egyptian bishop and two African regional councils.

$ Pope Sylvester I did not attend the Council of Nicea, in which the creed was established.

$ Emperor Constantine considered himself to be the thirteenth apostle.

$ Constantine was baptized on his deathbed by Bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia, a renowned heretic.