Chapter 5: Bottom Feeders

Relishing the Franks

That southerly breeze wafting gently across Europe in the early ninth century might just have been a huge sigh of relief emanating from Rome. The Church had cemented its relationship with Charlemagne and the succeeding Holy Roman Emperors, and, mirabile dictu, the Franks had made good on their promises. For the first time in centuries the pressure on papal holdings from the so-called barbarians was checked. Never mind that by any objective standard the Franks were probably less civilized than the Lombards. If they were barbarians, the Franks were at least Catholic barbarians, and that made them Holy, Roman, and Imperial. The Lombards and their ilk were just heathens.Although the popes of the 800’s could finally afford to consider issues other than survival, the Renaissance did not begin in the ninth century, and neither was there a rebirth of spiritualism. Over the centuries less effort was expended delineating orthodoxy and rooting out heresy. Western Christians may have even grown too ignorant to discuss theology. The schools Charlemagne had established early in the century died out. Soon only the clergy received any education worth mentioning.

Here are samples of a few of the tastier offerings of the somewhat bland ninth-century pontificates. Following these appetizers will be served dishes spicy enough for any palate.

St. Accomplice I

The pontificate of Paschal (or Pascal) I lasted from 817-824. I do not know how Sr. Mary Immaculata would explain the fact that he disinterred the bones of over 2,300 Christians who were considered martyrs. Legends differ as to whether God or a saint showed Paschal the location of the missing remains of St. Cecilia. Somebody’s skeleton was exhumed at the pope’s direction and placed in a church named for her in Trastevere. In 822 a judgment against the pope was issued by Lothair I, the King of Italy and co-emperor. The pope denounced it as illegal. Two papal officials, both senior priests, had testified in the proceedings. They were later found blinded and beheaded, surely a supererogatory punishment. The pope himself was accused of their murder. He swore an oath that he did not do it. “The Roman people have got to know whether their pontiff is a crook. Well, We are not a crook.” Evidently he did, however, know the identities of the perps, whom he protected because he considered the victims “traitors” for participating in the trial. In response the emperor clamped down on papal activity in Rome. The pope’s approval rating[1] dropped into the single digits. When his death was announced the next year, the assembled throng let out a cheer. His corpse was not even allowed inside St. Peter’s.Paschal granted the first papal indulgence. Its recipient could forgo some or all of the punishment in purgatory for venial sins. Eight hundred years had elapsed before a pope finally realized that his power of binding and loosing might reach to purgatory. Later popes would apply the whetstone to this seemingly innocuous tool of mercy and transform it into a deadly weapon.

Trial by Water

The one memorable innovation of Eugene II, the pontiff from 824-827, was the official sanctioning of the use of “trial by cold water.” When someone accused of a particularly odious crime refused to confess, a sizeable body of water – a pond, a lake, the Adriatic Sea, an old Roman bath, or whatever the Lord provided – was blessed and exorcised by a priest. Pope Eugene reasoned that water thus sanctified would repel guilty people, and they would therefore float. Any innocent person would be “accepted” down to the bottom of the body of water.[2] The accused, sometimes weighted down with a millstone, would be cast into the water. If the accused remained near the surface of the water, he/she would be extracted, and the sentence would be executed forthwith. If the subject was innocent and therefore sank, officials would attempt to retrieve him/her from the depths. It wouldn’t matter much whether the rescue effort succeeded. Anyone who drowned would die with a clean conscience and assurance of the Final Reward. It was a win-win-win situation.If the method seems a trifle medieval, it was surely more humane than the “hot water” and “fire” versions of trials by ordeal. In 1215 the Fourth Lateran Council prohibited trial by cold water, so it was officially approved by the Church for a little less than four centuries.

The Miracles of Pope Leo IV

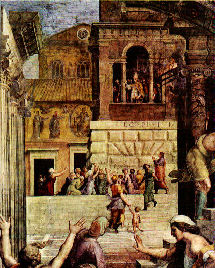

What a pity that Sr. Mary Immaculata never informed us of the deeds of Pope Leo IV, the saint who served as pontiff from 847 to 855! Today he is best known for the walls that he built around the Roman neighborhood that includes the Vatican, an area still known as the “Leonine City.” The sixteenth-century artist Raphael immortalized him in The Fire in the Borgo, which depicted him using the sign of the cross to extinguish a fire raging in the Anglo-Saxon area of the city before it spread to St. Peter’s Basilica. Pope Leo’s most astounding accomplishment has lately been neglected. Cormenin quoted a chronicler of that era: “A cockatrice of more than thirty feet in length and two and a half in thickness, had retired into a cave near the church of St. Lucius, to which no one dared approach, as the breath of the monster caused death. The pontiff, however, went in a procession at the head of his clergy to the cave where the cockatrice lay, and as soon as the animal heard the voice of the Holy Father, it died, casting forth a great flame from its mouth.”[3] Our class learned a little of St. George and his dragon but nothing of this feat of papal derring-do. It's a pity. Any story about a pope slaying a monster with deadly halitosis would have held our attention.Not everyone shares the conventional opinion concerning the saintliness of Pope Leo. Cormenin concludes his treatment of this pontificate with these remarks:

Other writers, equally commendable for their information, affirm that the Holy Father founded a convent of nuns in his own house, and that he abandoned himself with them to the most abominable debaucheries; they accuse him of having been of a sordid avarice, and they cite, to sustain their opinion, the testimony of the celebrated abbot, Loup-de-Ferriere. In fact, this monk, having been sent to Rome as an ambassador, took care to fortify himself with magnificent presents, “because,” said he, “without this indispensable precaution, one cannot approach Leo the Fourth.” Finally, historians maintain that the care of his personal safety, and not his solicitude for the people, was the only moving cause of the immense works which he caused to be executed in the Roman province.[4]

The Pope Who Returned from the Grave

When Adrian was succeeded by Pope John VIII, Formosus himself had been a candidate for the papacy. The new pope ordered Formosus and two other bishops to France to visit King Charles the Bald. This was evidently not simply a ploy to get a potential rival out of town. The trio brought with them an invitation for the king to journey to Rome to be crowned emperor.

A large contingent of highly placed Romans adjudged the occasion of the king’s visit a good time to vacate the Eternal City. Some had favored the imperial coronation of the widowed Empress Engelberga and Louis the German; they probably feared the wrath of the pope and/or the new emperor. Others were apprehensive that John VIII, never reluctant to wield power, might crack down on their shady operations in the city. The fugitives won no friends by absconding with Church riches.Although no one associated him with these groups, Formosus also made himself scarce. Perhaps a little birdie told him that a name that began with “F” and ended with “osus” was high on the pope’s enemies list. He never linked up with the other fugitives. Instead, he fled to the abbey at Tours, a singularly strange destination in a territory controlled by the new emperor.

Pope John convened a synod to deal with the fugitives. All were ordered to return immediately to Rome, but nobody complied. A second synod then charged Formosus with aspiring to the bishopric of Bulgaria and the Papal See, opposition to the emperor, desertion of his diocese, despoiling of Roman cloisters, saying Mass while under interdict, and conspiracy in the proposed destruction of the Papal See. He was convicted,[7] defrocked, and excommunicated.In 878 Pope John and the synod lifted the excommunication, but only after Formosus swore never to return to Rome or perform any sacerdotal functions. He was out of circulation until John VIII passed away in 882. His successor, Pope Marinus I (also known as Martin II), immediately released Formosus from his oath, restored his diocese, and summoned him to Rome. Marinus was succeeded by Adrian III and then Stephen V (VI). Formosus kept his nose clean throughout their pontificates. He was elected pope by the people and the clergy of Rome in 891, the first former excommunicant, as far as we know, to become pontiff.

Pope Formosus inherited a number of thorny problems. He initiated few new policies, but dealing with fallout from his predecessors’ actions placed him in uncomfortable situations. Back in 870 the Eighth General Council had declared that Patriarch Photius of Constantinople had never been a legitimate bishop. It fell to Pope Formosus to order members of the eastern clergy ordained or appointed by Patriarch Photius[8] to resign their offices. This news was not appreciated by those affected, even though Formosus granted them absolution if they repented. Formosus also became embroiled in conflicts over the imperial crown. Commitments made by Pope Stephen obligated Formosus to crown as emperor Lambert, the very young Duke of Spoleto, an Umbrian town seventy-eight miles from Rome. In 895 King Arnulf, the Carolingian[9] successor, invaded Italy at the pope’s request. The next year Formosus crowned Arnulf as emperor. This duplicitous act did not sit well with Lambert and especially his mother Agiltrude.Formosus died on April 4, 896, but he was not soon forgotten. The next pope, Boniface VI, reigned for only fifteen days. He reportedly died of the gout, but his illness may have been aggravated by involuntary amateur surgery practiced by the Spoleto henchmen.[10] Boniface’s inclusion in the papal roster is somewhat hard to countenance. He had been defrocked twice, and at the time of his papal investiture he had evidently never been reinstated. Moreover, a papal council later invalidated his selection.

After suffering a stroke in 897, Arnulf departed from Italy. Agiltrude was able to rebuild her authority in Rome. Following Pope Boniface was Stephen VI (VII), who attained the pontificate by aligning himself with Agiltrude. She was still furious at Formosus, and she prevailed upon Stephen to help her wreak vengeance on him, or at least on his remains. Margaret Hamilton has been dead for decades, but if a movie were made about this incident, it is hard to imagine anyone else portraying Agiltrude. Maybe Margaret could be CGIed in. Pope Stephen called a meeting of the bishops of the area, the notorious “Cadaver Synod.” He ordered poor Formosus’s body, which had been decomposing for months, removed from its sarcophagus, clothed in papal vestments, and propped up on a throne. He then appointed a deacon as Formosus’s defense attorney. He himself assumed the role of prosecutor as well as that of co-judge.[11] The charges echoed the ones that John VIII had leveled a quarter of a century earlier. Even someone who flunked moot court could imagine some pretty persuasive arguments for the defense – double jeopardy, the decrepit physical state of the defendant, the fact that he never actually became archbishop of Bulgaria, etc. However, the deacon tasked with defending Formosus never uttered a word. Who could blame him? He may have feared that the only way to avoid retching was to keep his mouth clamped shut.Formosus’s corpse was convicted. The papal vestments were torn from the cadaver. The three fingers with which he had consecrated the host were broken off of his hand. His remains were flung into the Tiber. The carcass was, however, fished out downstream and preserved by sympathetic monks.

Formosus’s pontificate was totally nullified; the synod reversed all his papal and episcopal pronouncements. The ceremonies for the priests whom he had ordained and the bishops—presumably including Pope Stephen himself, whom he had consecrated—were declared invalid. Those baptized or absolved by one of these clerics would surely be nervous about their prospects when they approached the Pearly Gates. This theater of the absurd got “two big thumbs down” from ordinary Romans. Pope Stephen was imprisoned by an angry mob and shortly thereafter strangled. Sergius, an active participant in the Cadaver Synod, was elected to succeed Stephen, but he was immediately ousted by the pro-Formosus faction. Sergius was not even pope long enough to make the official list. Nevertheless, he survived the revolt and, in fact, was the instigator of the farce’s madcap finale. The next pope, Romanus, was in office such a short time that he accomplished essentially nothing.[12] His successor, Theodore II, was the son of Photius I, the notorious Patriarch of Constantinople whom Pope Nicholas I anathematized and whom the Roman Church has blamed for the Great Schism. Theodore’s pontificate only lasted twenty days, but not only did he manage to get Formosus’s corpse entombed again in St. Peter’s; he also called a synod to annul all decrees of the Cadaver Synod. Formosus’s pronouncements and ordinations were reinstated. The next pope, John IX, confirmed these judgments. But the tale does not end there. In fact, hold onto your hats, because the action-packed tenth century, arguably the most outrageous period in papal history, is about to commence. Pope John IX died in 900. Benedict IV, a strong supporter of the man who had ordained him, Formosus himself, followed John. In 903 Benedict was succeeded by Leo V, who was ousted within a few months by a man named Christopher. The latter found the throne of Peter to be a perfect fit for his own backside and incarcerated Pope Leo. Christopher’s self-appointment did not disqualify him from the official list of popes. He was ousted by the Theophylact faction (much more about them later) in 904. Sergius had not been idle since his first papal election. Although excommunicated by Pope John IX, he got himself installed as Pope Sergius III for a second time in 904. That the Roman clergy overlooked Sergius’s transgressions would not surprise Sr. Mary Immaculata. After all, the prelates were experts on the scriptures, and in Matthew’s gospel Jesus indicated that his followers should forgive sinners 490 times.[13] The fact that Sergius had been hand-picked by the strongest Roman faction may also have entered the equation.Pope Sergius threw Pope Christopher in prison. Did he appreciate irony enough to make Christopher share a cell with Leo? Unfortunately the record is not clear about either deposed pope’s fate. Both may have died in prison, one or possibly even both at Sergius’s order.

One of the first entries in Sergius’s pontifical day planner was a note to reopen the case of Pope Formosus, whose corpse had by then been undisturbed for eight years. Pope Sergius promptly reinstated his own verdict of the Cadaver Synod and again voided all of Formosus’s ordinations as well as his other official acts. Once again, it seemed to have slipped the pope’s mind that he himself had been consecrated as a bishop by Formosus. It is safe to say that at that point no one in western Christianity knew who was a legitimate priest and who was not.Some have alleged that Sergius had Formosus disinterred again, beheaded, and thrown back in the Tiber. In any event what was left of Formosus’s corpse eventually did manage to find its way to a crypt in St. Peter’s, which is where it will remain unless some future pope takes a notion to convene another Cadaver Synod. There seems to be no statute of limitations on crimes like coveting a Bulgarian bishopric.

Theodora and Marozia Turn a Few Pontifical Tricks

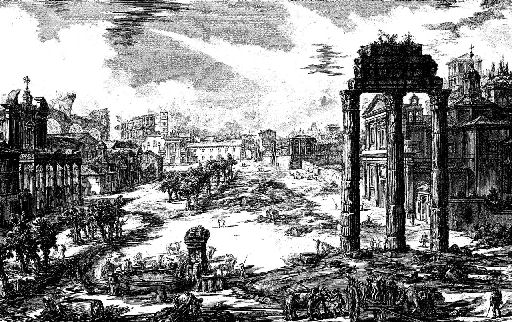

By the beginning of the tenth century Rome was a mess. The city’s population and importance had shrunk to a small fraction of the levels of the empire’s heyday. No industry and little commerce remained. If not for the papacy and the revenue from pilgrimages, Rome might have become a ghost town, as happened to its once thriving neighbor, Ostia. The engineering and architectural techniques responsible for the marvelous edifices of the Roman empire had long been forgotten by the Romans. When they needed to construct or repair a building, they simply cannibalized materials used in the magnificent imperial structures. E.R. Chamberlin painted this picture of the period:

After the collapse of the empire the city suffered endless sacks,[14] but it was the Romans themselves who dismantled the classical city and that for the most humdrum of reasons – marble, when burned, yields lime which can be used for plaster. The scores of limekilns in the city were each fed by irreplaceable fragments of past glory. The great blocks of travertine that formed the core of the walls were broken up to make byres and hovels. Those columns that escaped the limekilns, or were not incorporated into new churches, lay where they fell, protected at least by the accumulated rubbish. … A contemporary of Augustus or Nero … would have been appalled by the filthy conditions of the streets themselves. Many were permanently blocked by collapsed buildings; all stank in high summer. The city that had known the splash and play of countless fountains now endured an endless drought, for the great aqueducts were ruined.[15] Roman politics in this period was more than a little complicated. The conflict over who would be recognized as the Holy Roman Emperor persisted. The power to designate the emperor seemed to rest with the pope; at least the popes claimed that right. The major contenders were again the Carolingians and the Duke of Spoleto. Theophylact, the count of Tusculum, a noble with connections to the original empire, had emerged as a rather strong leader in the city. His title was Senator of Rome, but the real power seemed to be his wife, Theodora. They had two daughters, Marozia and Theodora. Marozia became a very important person in her own right. The younger Theodora’s principal historical roles were to breed a powerful line of descendants and to confuse historians.[16] The Senator supported the notorious Sergius III in 904 and pulled strings to get him installed at the expense of the long-suffering Leo V and Christopher. This began a long intimate association between the Theophylact family and the papacy. History has assigned Theodora (the mother) and Marozia incredibly bad reputations. They were both called strumpets by Liutprand (sometimes spelled Liudprand), the Bishop of Cremona. Evidently Marozia, at the tender age of fifteen,[17] became Pope Sergius’s mistress and bore him the child who eventually became Pope John XI.

* * *

Time, ref.

Theophylact? Theodora? Liutprand? What kind of Italians would curse their bambini with names like those? Well, Theophylact and Theodora are obviously Greek in origin. In the early eighth century a famous exarch named Theophylact made an official visit to Rome; maybe he left a microscopic memento in one of the ladies in Tusculum. Descendants of the Theophylact family with more euphonious names remained influential throughout the centuries. Bishop Liutprand shared the name of a powerful eighth-century king of the Lombards. Cremona is fifty-five miles southwest of Milan, one of the Lombard capitals. Many Americans think of Italians as a homogeneous race of pasta-eating, wine-drinking singers and mobsters. For centuries, however, Italy was Europe’s melting pot. Many uninvited visitors brought large armies with them,[18] and vows of chastity were almost never required for participation. Bishop Liutprand remains the primary source for much of our knowledge of this era. Think of him as a bishop on a chessboard rather than a bishop in a cathedral. On a clear day he probably could have found the duomo in Cremona, but his primary job was minister without portfolio for Otto I, the German King. He entered into Otto’s service in 955 after a youth spent first in the courts of Hugh of Provence[19] and then in those of Berengar II, the ruler of much of Italy. Changing princes was a propitious move for Liutprand; Otto defeated Berengar in 951 and eventually became Holy Roman Emperor. Otto appointed Liutprand bishop.Anyone studying the tenth-century papacy must determine how much to trust Liutprand’s accounts. He knew his subject matter, he was present for most important events, including the historic councils, and he was personally acquainted with many influential participants. On the other hand, he was a vindictive man who hated Berengar and his wife and disparaged Romans and their lifestyle. And when it came to shading a story to further his own political purposes, Liutprand could compete with twenty-first century spin-doctors.

Back to the popes.

* * *

The two popes after Sergius III were Anastasius III and Lando, both short-timers who died mysteriously, a common fate in the tenth century. Next came John X, chosen by Theodora (the mother). Before he became pope, a peculiar relationship had blossomed between the pair in Bologna and Ravenna. He was also evidently related to her family in some way. Liutprand claimed that they were having an affair, but the bishop suspected almost everyone in Rome of promiscuity. Maybe she just liked the cut of John’s jib. His pontificate lasted fourteen years, easily the endurance record for the tenth century. He seemed to devote most of his time negotiating a complicated set of political entanglements. In the end he sided with Hugh of Burgundy.Meanwhile, Marozia employed her marriage bed to fashion her own alliances. First she married Alberic, the Duke of Spoleto. He died in 926. Shortly thereafter she latched onto Guido (now you’re talking!) of Tuscany, who died in 929. Her third husband was Hugh of Provence. She had two sons that we know of, John, whose father was probably Pope Sergius III, and Alberic, sired by Alberic of Spoleto.

There are just too many Alberics[20] in this chapter. So, I propose to designate Alberic of Spoleto as “A1”, Alberic the son of Marozia as “A2”, and the Alberic who appears in the eleventh century as “A3”. There was also a Bishop of Milan named Alberic, but he does not merit a number. If he wanted one, he should have done something outrageous.By 928 Marozia held the titles of Senatrix and Patricia of Rome. She was the boss, period. Her top priority was to remove Pope John X. She enlisted her hubby Guido’s help in this endeavor. First, John’s brother Petrus, the prefect of Rome, was assassinated in June. Shortly thereafter Guido’s men seized the pope himself and provided him housing with a stylish iron door. He died therein within a year. According to Liutprand he was suffocated with a pillow. Flodard of Reims has written that he died of “anxiety.” You would be anxious, too, if you were tied to a bed in prison, and someone came at you with a pillow. Incidentally John never resigned, and he was still alive when each of the next two popes were enthroned. Nevertheless, all of them are considered legitimate popes. Let’s not waste S’ter’s time with this trifle; things are getting interesting.

Marozia chose a Roman noble named Leo VI to succeed John X. He only lasted for seven months. Then she picked Stephen VII (VIII), who was healthy enough to endure until 931. By then Marozia’s own illegitimate son John was twenty-five and ready to assume the papacy. He wasn’t a priest, much less a bishop, but his dad had been pope, and his mom, who always had a “can do” attitude, ran Rome. Getting John up to the episcopal level only required a couple of days of non-stop ceremonies. Then he ascended the throne of Peter as Pope John XI.Marozia had by then overcome her grief over the death of second husband, Guido. She wanted to marry Hugh of Provence, the King of Italy, who was Guido’s half-brother. By the canonical laws of the day, the marriage was incestuous – without a papal dispensation. Pope John brooded over the theological, philosophical, and moral implications for a few seconds and then gave the happy couple the go-ahead. In fact, he performed the nuptials himself, the only time that a pope ever presided at his own mother’s wedding ceremony.

Hugh brought his whole army with him to Rome and encamped them outside the walls during the festivities. The groom reportedly derided the oafishness of A2, who had become a fairly powerful figure in his own right. Nobody dissed A2, not even his new step-dad. The young man craved revenge. However, he may have also feared that his mother’s new husband might blind him, an accepted way of forestalling one’s potential enemies in the 900’s. In 932 or perhaps 933, A2, although barely twenty at the time, mustered an army and assaulted Castel Sant’Angelo, his mother’s headquarters. Hugh and his army fled. A2 captured Marozia and incarcerated her. He also kept his half-brother the pope on a short leash. Pope John performed his priestly functions, but A2 managed all the politics – including Church politics – himself. A2 even determined the prelates who received the pallium. John XI died at the age of thirty in his virtual prison. A2 selected the next four popes himself: Leo VII, Stephen VIII (IX), Marinus II, and Agapetus II. All were rather nondescript, except for Stephen. According to the historian Martin of Poland, Pope Stephen’s nose was cut off in an insurrection in Rome. Imagining the circumstances surrounding such an event is challenging. The vision of Moe Howard seizing Larry Fine’s proboscis between his knuckles is difficult to dismiss, as is the recollection that the nose of Lee Marvin’s character in Cat Ballou had been bitten off in a brawl. Maybe the pope frequented bars on the wrong side of the Tiber, and something similar befell him. Unable to locate a suitable metallic prosthesis, Stephen was too ashamed ever to appear in public again.Marozia expired in prison, probably during Pope Leo VII’s pontificate. During Agapetus II’s papacy, A2 apparently began to sense intimations of his own mortality. He had ruled Rome for over thirty relatively peaceful and prosperous years. All Roman nobles were indebted to him in one way or another. In 954 he made the pope and Roman nobles swear that they would elect his illegitimate son Octavian as the next pontiff. When A2 died on August 3, Octavian immediately assumed his father’s offices of Prince[21] and Senator of Rome. In October of 955 Pope Agapetus also approached the Pearly Gates.

Dude, Like Chicks Go Wild When They Kiss My Papal Ring

Octavian’s date of birth is unknown, but he probably was no more than eighteen when he was consecrated, for lack of a better word, as pope on December 16, 955. Was Octavian the youngest pope? Maybe. The ages of many popes are unknown, but one can hardly imagine other circumstances in which a teenager would be selected. The equally astounding story of another juvenile pontiff will follow shortly. Oddly, Octavian may not have even been the youngest patriarch in the church. “At the same time, the See of Constantinople was occupied by Theophylactus, a patriarch of sixteen years, who ruled over the corrupted clergy of the Greek church.”[22]

At the time of his election Octavian had not yet been ordained a priest. Who would receive sacraments from an eighteen-year-old punk? His investiture therefore required that he follow the fast-track through the clerical hierarchy laid for his uncle, Pope John XI.The name “Octavian” is absent from the list of popes. When the young man became pontiff, he changed his name to John, which made him Pope John XII, or, as he probably preferred, Popemaster J.[23] Only one pope had previously taken a new name at his investiture. Doing so was counter to canonical laws of the day. The emphasis is on “was,” because in the 900’s the pope could adjust the canons at will, especially if he was simultaneously the Prince of Rome.

Not many encyclicals can be found with John XII’s signature and seal at the bottom. As Prince of Rome Octavian could already do everything he really enjoyed – hunting, gambling, and carousing. Adding the papacy to his résumé could seriously crimp his social life. Nevertheless, he resolved to make the best of the situation. Liutprand wrote that he turned the Lateran Palace, the pope’s traditional residence and the centerpiece of the real Donation of Constantine, into a brothel. John paid little or no attention to any laws. He was accused (and later convicted by a synod of bishops) of a few minor youthful indiscretions including simony, theft of sacred objects to be used as presents for prostitutes, adultery, incest (with practically every relative imaginable), blasphemy, and murder. He made a bishop out of a ten-year-old boy to whom he felt affection.[24] Pope John appointed his horse as Senator. I would not be surprised if he trashed a few hotel rooms in his day, as well. His pontificate might have survived even this impressive rap sheet. As A2’s son, he enjoyed considerable local backing, and the saying in the tenth century was “What happens in the Lateran Palace stays in the Lateran Palace.” However, John XII was the first pontiff who, as Prince and Senator, had at his disposal something resembling an army. Rome in the 900’s could get dreadfully dull for a young man when no pilgrimage was in town. The Popemaster occasionally liked to go cruising with his army in order to expand the papal holdings at the expense of a few nearby villages. He ordered a lackey to polish up the papal armor, had the papal blacksmith take in his chain mail a link or two in the waist, mounted Senator Equus, and led the troops himself. The pope’s army in no way resembled the legions of the empire’s salad days. A more accurate depiction would be a bunch of underemployed goombahs with nondescript weaponry. In tenth-century central Italy, however, that was enough to make some noise.The pope’s military escapades attracted the attention of the King of Italy, Berengar II, Liutprand’s old boss. Berengar had a real army at his disposal, and it easily defeated the pope’s ragtag outfit near Ravenna. However, Popemaster J had a few tricks up his camisia. He offered the crown of the Holy Roman Empire to Liutprand’s new employer, King Otto, who directed his army over the Alpine speed bump and entered Rome on February 2, 962. The young pontiff crowned him emperor on February 13. Shortly thereafter Otto affirmed the territorial rights of the Papal State and even increased its reach with his own “Donation.” In return the pope pledged fealty to the emperor. “Word.” Otto declared that all popes would swear the same oath. “Whatever.” German beer and Italian wine flowed freely in celebration. “Sweet.”

Not long after Otto returned to Germany, Popemaster J’s trickery got a little too cute. He approached Berengar about forming an alliance against the emperor. He even drew up proposals to the hated and feared Magyars. Worse yet, he put his overtures in writing! Several papal messengers were intercepted by the imperial cavalry, and word got back to Otto. When the emperor returned to Italy, the pope threatened to excommunicate him. Undaunted, Otto marched on Rome. The Holy Father gathered up as much of the Church’s treasury as he could carry off and fled first to Tivoli and then to the island of Corsica. In November of 963 Otto solemnly convened a council of bishops in Rome. Liutprand recorded the results of this council in considerable detail, and his monograph Historia Ottonis can be read today. John was convicted of a laundry list of heinous crimes and deposed. One of John’s associates, a layman named Leo, was then elected pope. He underwent the now familiar practice of being made sub-deacon, deacon, priest, bishop, and cardinal in a day or two. Then he was enthroned as Pope Leo VIII. Many Romans, nobles and commoners alike, nurtured anti-imperial feelings. They also were sick of the relentless series of invasions from Germany. Brooking none of this Teutonic interference in what they considered a purely local Roman matter, they rose up against Leo and assailed Castel Sant’Angelo. It wasn’t pretty; Otto’s troops were redwashing the castle’s bridge across the Tiber with freshly spilled Roman blood when Leo himself put an end to the massacre. After that, things settled down, and Otto reckoned that the trouble was over. He left town.Meanwhile Pope John had found “excommunication” in his Pope’s Handbook. He read the formula and excommunicated in absentia everyone at the 963 council. He invalidated all their decrees. When the coast was clear, John returned to the city and fomented a second uprising against Pope Leo; this one succeeded. John called another council of sixteen bishops, eleven of whom had participated in the previous council that had deposed him. This council deposed Pope Leo and reinstated John XII as pope on February 26, 964. Leo fled for his life.

Shortly thereafter fate intervened. Popemaster J was caught flagrante delicto with a young lady named Stephanetta.[25] Her husband evidently came home from the chariot races a little early. What transpired next is the subject of conjecture. Many claimed that the cuckolded spouse threw the pope out the window or throttled him with a cudgel of some sort. Some said that the pope, although still in his early twenties, had a stroke. Others reported that the devil himself took His Holiness’s life, although it is hard to comprehend why the Prince of Darkness would want to terminate one of his best disciples. Until John’s death turns up as one of the “Cold Case” files, we will probably never know. Suffice it to say that the papacy of John XII was over for good. At least he went out with a bang. A third council of bishops proclaimed a somewhat obscure Roman cardinal named Benedict as pope on May 22, 964. Even though Benedict enjoyed a good reputation,[26] Otto said “No dice.” After all, Benedict had voted for Pope Leo and had sworn to support him. The emperor laid siege to Rome, which quickly yielded. He then personally deposed Benedict on June 23, released Pope Leo from prison, and reinstated him as pontiff. Leo immediately confronted Pope Benedict V. He ripped the pallium off of his rival’s shoulders, seized his ferula (the distinctive shepherd’s crook), and broke it in two.[27] Pope Benedict glanced over to determine the emperor’s reaction to this outrageous behavior. Otto’s chin almost imperceptibly nodded, which Pope Benedict took to indicate that the emperor would not interfere in the dispute. Supremely confident of his skills in unarmed combat, Benedict launched a mighty leap and skillfully applied a flying head-scissors to the stunned Pope Leo. This was it; two legitimate popes, but only one would survive the first mano-a-mano conflict in the history of the pontificate – a fight to the death with no holds barred.Well, not exactly. According to Claudio Rendina, Pope Leo really did strip Pope Benedict of his pallium and break his staff in two. However Pope Benedict’s reaction was not as aggressive. He dropped to his knees, seized the emperor by his legs, and begged forgiveness. This pitiable action earned sympathy from the emperor, but not from Pope Leo. If it had been up to His Holiness, Benedict would most likely have paid a dear price for his treachery, but instead, the emperor brought Pope Benedict back to Germany and thus deprived the Romans of any reminder of the pope whom they had elected.

Leo only survived until January 3, 965, but no papal election was held in Rome to determine his successor. Six months later Benedict abandoned this mortal coil. At that point no matter whom you supported, there was a dead pope for you to mourn. Benedict’s death dispelled the confusion. No one publicly questioned the legitimacy of Otto’s personal selection, the erstwhile Bishop of Narni, Pope John XIII, who was known as “The White Hen”[28] because of his hair color.Both Leo VIII and Benedict V are recognized as popes. John XII’s second pontificate is not recognized by the Church, and neither is the council that he called after retaking the papacy. Oh, one other thing: Otto decreed that in the future no pope could take office without the emperor’s approval. The shoe was back on the other foot.

I think that Sr. Mary Immaculata may be napping. It has been a hard day. Let’s not disturb her right now.

Now You See Them, …

The greatest papal trickster of all time was named Donus II. His entire repertoire consisted of only one trick, but the effect has never been matched in the two millennia of the papacy. It is safe to say that no pope is ever likely to duplicate this stunt.An official book published in Milan in 1925 with short biographies of each pope from St. Peter to Pius XI contains a nice little sketch of Donus in profile. His Holiness is wearing the papal tiara and brocaded vestments. His nose is a little on the W.C. Fields side, but otherwise his appearance is unexceptional. The text reads as follows: “After the expulsion of the schismatic antipope Boniface VII, and the death of pope Benedict VI, was elected pontiff Donus II, a Roman, who governed the Church for a little more than three months. In this very brief period the history of the Papacy does not record any event. He was buried in Saint Peter’s.”

The descriptions of quite a few pontificates are similarly nondescript. Several popes served even less than the three months of Donus’s reign. Ten popes – Stephen II, Urban VII, Boniface VI, Celestine IV, Theodore II, Sisinius, Marcellus II, Damasus II, Pius III, and Leo XI – did not last a month. Even in the twentieth century Pope John Paul I survived for only thirty-three days. The fact that Donus II was unable to accomplish much was unremarkable in the tenth century. Therefore, nothing about the entry for the second Pope Donus attracted much scrutiny from papal scholars.

In 1947 the Vatican published a new edition of Annuario Pontificio. Surprisingly, the list of popes was a couple short of the number on the previous list. One was St. Anacletus,[29] who had been suspect for some time. A side-by-side audit revealed that Donus I had lost his Roman numeral, and Donus II was entirely absent. Inquiring minds wanted to know: what became of Donus II? Did the Church fathers suddenly consider him an antipope? No, he was actually declared to be a non-pope, in fact, a non-person; he never existed at all. Evidently a scribe at some point mistakenly wrote DOMNUS when he intended to write the common Latin word DOMINUS, which means Lord. Then someone else interpreted DOMNUS as an alternative spelling of DONUS, and a person who was never born began to take shape in people’s minds. Who drew his picture and on what did he base it? He reminds me of a chunkier version of Phineas T. Bluster, the marionette that terrorized the dreams of my youth, minus the spectacles and plaid vest. Equally mysterious is who came up with the idea that Pope Donus was a Roman and that his pontificate lasted “a little more than three months.” Everyone in our class would have loved to ask Sr. Mary Immaculata who, if anyone, is buried in his tomb in St. Peter’s.You might think of Pope Donus II as a one-trick phony.

One question remains: If Donus was not elected when the previous pope died in 973, what did happen? Well, one event that certainly occurred in 973 was the death at age sixty-one of the great Holy Roman Emperor, Otto I. The reign of the last pope approved by Otto, Benedict VI, began in January of that year. Benedict resided in Rome, but he was of German descent. As soon as word of Otto’s demise reached Rome, a local named Crescentius fomented a revolt against the pope. Crescentius headed the Theophylact clan. His mother was Theodora, the “other daughter” of the original Theophylact and Theodora. That made Crescentius, by my reckoning, A2’s cousin and the second cousin of both Pope John XI and Pope John XII. Furthermore, Pope John XIII, whom Otto had appointed as pope, was also Crescentius’s brother. In 967 the emperor’s twelve-year-old son Otto II had been crowned as joint emperor by a grateful Pope John XIII.The revolt against Pope Benedict VI succeeded. The pontiff was captured, deposed by the conspirators, and incarcerated in Castel Sant’Angelo. A deacon named Franco was elected pope. His investiture in June of 974 proceeded without Otto’s approval. When Franco assumed the pontificate he took the name Boniface VII. In July Pope Benedict was found strangled in his cell. Legend has it that Pope Boniface did him in with his own hands.

A counter-revolt was led by the pro-imperial forces in Rome. Boniface saw the handwriting on the wall. He packed up the most readily fungible Church treasures and blew town. He next turned up in Constantinople.

The replacement pope was named Benedict VII. Although he was not the emperor’s first choice, Otto II confirmed him in October of 974. Benedict was by most accounts a pretty good pope. He is not a saint, but it is hard to find much dirt on him, and in the tenth century that is really saying something. He was followed in 983 by another German named Peter, who hailed from Pavia, the former capital of the Lombard state in northern Italy. When Peter was confirmed as pope, he took the name of John XIV. His extreme misfortune was to be the pope at the time of the premature death in 984 of Otto II, who had become nearly as powerful as his famous father. His own son and heir, Otto III, was still a child. As soon as news of the death of the second Otto reached Boniface, he set sail for Rome, where he joined forces with the Crescentius family. Castel Sant’Angelo once again became the inhospitable domicile of a pontiff, this time John XIV. Somehow he got poisoned during his stay there; you just had to watch your diet carefully in those days. The Roman clergy felt no need to vote Boniface in again. He simply decreed that during his entire nine-year absence he had been pontiff all along and that both Benedict VII and John XIV had been antipopes. For a while nobody seemed to question his right to govern the Church. However, in 985 the Crescentius family tired of his act. Boniface was seized, and his body was beaten and mutilated. It was then dragged through the streets of Rome and dumped first at the foot of the statue of Marcus Aurelius on horseback[30] and then in the courtyard of the Lateran Palace. At some point during this journey the spark of Boniface’s life was extinguished.The Sorcerer and His Apprentice

By the time that Pope John XV’s investiture cleared up the mess of papal succession, the French Church had had enough of the pontiffs’ shenanigans. A synod of the French bishops held in 991 protested the state of the papacy. Its secretary, a young priest named Gerbert, recorded a speech by the Archbishop of Orleans that included the following:But the Church of God is not subject to a wicked pope; nor even absolutely, and on all occasions, to a good one. Let us rather in our difficulties resort to our brethren of Belgium and Germany than to that city, where all things are venal, where judgment and justice are bartered for gold. Let us imitate the great church of Africa, which, in reply to the pretensions of the Roman pontiff, deemed it inconceivable that the Lord should have invested any one person with his own plenary prerogative of judicature, and yet have denied it to the great congregations of his priests assembled in council in different parts of the world. If it be true, as we are informed by common report, that there is in Rome scarcely a man acquainted with letters without which, as it is written, one may scarcely be a doorkeeper in the house of God, with what face may he who hath himself learnt nothing set himself up for a teacher of others? In the simple priest ignorance is bad enough; but in the high priest of Rome, in him to whom it is given to pass in review the faith, the lives, the morals, the discipline, of the whole body of the priesthood, yea, of the universal church, ignorance is in nowise to be tolerated .... Why should he not be subject in judgment to those who, though lowest in place, are his superiors in virtue and in wisdom? Yea, not even he, the prince of the apostles, declined the rebuke of Paul, though his inferior in place, and, saith the great pope Gregory, if a bishop be in fault, I know not any one such who is not subject to the holy see; but if faultless, let every one understand that he is the equal of the Roman pontiff himself, and as well qualified as he to give judgment in any matter.[31]

Pope John XV declared the results of the council null and void and overruled its nomination of Gerbert as Bishop of Reims. Gerbert was forced to abdicate his see. The next pope, Gregory V, never understood how a country that appreciated Jerry Lewis’s talents could speak so badly about the pope. He not only banned French fries from the papal table, he threatened to interdict the entire nation of France.Fortunately, Gerbert soon acquired a powerful patron in the young emperor Otto III, who employed him as tutor and confidante. Otto helped Gerbert get back in the good graces of the Holy Father. Shortly thereafter, the emperor appointed Gerbert bishop of Ravenna.

Pope Gregory died in 999. Otto, who had brought his army to Italy with him, asserted his right to determine the Church’s leader through the millennial transition. He picked his tutor and his idol, Gerbert, who took the name Sylvester[32] II. Gerbert of Aurillac was perhaps the most brilliant European of his age, or at least the most brilliant western European cleric. He was certainly among the best educated. A native of France, he had studied extensively in Spain, the southern part of which was then controlled by the Saracens. He learned algebra and the principles of clockworks in Islamic schools. The majority of western Europe that was not under Islamic control was unbelievably backward. The only schools worth mentioning were in the cathedrals, and the only course of study that they offered was in religion. A man’s goal in life was to save his soul. Why bother studying anything else? Gerbert, in contrast, could do routine arithmetic in his head and used his abacus for more complex problems. Even the most educated clergymen would likely need sticks[33] to figure out the answer to simple addition problems. Gerbert probably had acquired texts with formulas in them, not magic formulas as was widely suspected, but algebra, which was also invented by the Arabs. He had more gadgets than Batman. He built clocks and installed an organ when practically no mechanical devices could be found in Italy. He rediscovered the astrolabe, which astounded his contemporaries. He allegedly kept in his study a brass head that answered yes/no questions. None of this would have today garnered the million dollar prize offered for proof of paranormal powers,[34] but Cardinal Benno, writing a century after the fact, called Pope Sylvester a sorcerer. In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king; to the ignorant the simplest science is indistinguishable from magic. At the age of sixteen Gerbert’s young patron, Otto III, had first come down to Italy in 996 to install his twenty-five-year-old cousin Bruno as Pope Gregory V. Like many visitors to the peninsula he fell in love with the country. He dreamt of restoring the old concept of the Holy Roman Empire. In his vision the emperor resumed his role as defender of the faith articulated by the pope. He was happy to be the iron fist in the pope’s velvet glove. As soon as Otto left Rome, the reigning member of the Crescentius family, also named Crescentius, deposed Gregory and installed an antipope, John XVI. Otto returned to Italy in 998, and he promptly relieved Crescentius of his head. John was allowed to retain his noggin, but just about every useful appendage – his nose, ears, eyes, and tongue – was severed. He was sent into exile, and he somehow survived in this accursed condition for fifteen excruciating years. After Gregory was restored to the throne of Peter, Otto moved his imperial headquarters to Rome, where he established residence. As usual, however, rule by a foreigner, even a well-meaning one, irritated the Romans. A mob eventually forced Otto to flee to Ravenna, where in 1002 he died frustrated in his vision of restoring the Holy Roman Empire.Pope Sylvester died about a year later. It is not unlikely that the Crescentius family might have helped his demise along. For centuries legends abounded about Pope Sylvester’s magical powers, including his ability to predict the date and location of his own death.

The Opening Acts

Eleventh century Rome was little more than an underpopulated town with many dilapidated buildings. After the execution of the second Crescentius, his son, generally called John Crescentius, took charge of the civilian government.Think of him as the capo of the era’s dominant street gang. He influenced the appointment of Sylvester’s first three successors:

• John XVII had been married and had three sons who grew up to become priests. His half-year pontificate was not especially memorable.

• His successor, John XVIII, was the son of a priest. Like modern popes he was already a bishop when he became pope. He served from Christmas 1003 until June 1009. Some reports say that at the end of his pontificate he got disgusted with the world and retired to a monastery. • Before his papal investiture Sergius IV was known as “Peter Pig-snout.” The news that Caliph Hakim had desecrated holy places in Jerusalem devastated him. He called a crusade to reclaim them, but nobody was interested. He died in 1012, as did John Crescentius.What was the Holy Roman Emperor doing during this period? Nothing; there was no emperor. Otto III had no offspring, and he died without naming a successor. His cousin Henry II, the duke of Bavaria, eventually amassed enough power to be called King of Germany. However, for a time so much was on his plate that the election of the bishop of a decrepit town in central Italy merited little attention.

Gregory, the patriarch of the Theophylact family in Tusculum, had been named a count by Otto III. Pretty good sources indicate that Gregory was probably the grandson of A2. If so, that would make Popemaster J his uncle.[35] Gregory appointed his son, also named Theophylact, as Pope Benedict VIII. The Crescentius family installed its own pope, who was also named Gregory. The gang that supported him chased Pope Benedict from Rome, but Pope Benedict promised King Henry the imperial crown in return for his support in Rome. A sojourn in Italy sounded good to the German monarch, so he headed south, restored Benedict to the throne of Peter, and climbed back over the Alps with a shiny new crown. Henry confirmed the papal “donations,” but he also reserved the right to approve or veto the selection of future popes.Pope Benedict’s relatives did not let the grass grow under their feet. Count Gregory built a Roman fleet and named himself admiral. The pope himself took command of the army. His younger brother Romanus ruled the city of Rome. The papal army won an important victory over the Saracens in 1016. The navy and the fleets of Pisa and Genoa successfully engaged the Arab fleet off the coast of Sardinia. The pope also persuaded Henry II to return to Italy to stop the advances of the Byzantines in southern Italy. One of the few legacies of Benedict’s papacy not earned on the battlefield was the condemnation of simony, the long-established policy of selling clerical offices. However, his condemnation did not stifle the practice.

Pope Benedict died in April of 1024. The emperor died two months later. Count Gregory appointed his second son Romanus to the papacy as John XIX. In order to assure support for Romanus, the family prudently ignored the ban on simony and distributed cash among influential Romans. It worked.Romanus wasn’t a priest, but this was no longer a serious impediment. He reportedly became a deacon, priest, bishop, and pope, all in one day, which still stands as the world record. As Pope John XIX he crowned Conrad II as the Holy Roman Emperor. When Romanus became pope, the civilian authority in Rome was handed over to a third brother, Alberic, the long-awaited A3. When Pope John XIX died in 1032, it was A3’s turn.

The Once and Future Pope

Like A2, A3 wasn’t after the papacy for himself; he was content to manage the civilian sector. Instead he expended a fortune buying votes for his young son, whose name was – wait for it – Theophylact. How young? Well, the Church claims that he was around twenty. Others have reported that he was as young as eleven. It would take Sr. Mary Immaculata’s acumen for divine mysteries to explain how a kid still eligible to play Little League ball could possibly be confused with a junior in college. At any rate, when he became Pope Benedict IX, either he or his great uncle Octavian was in all likelihood the youngest pope ever.

Benedict’s conduct was so bad that many have compared it unfavorably with the Popemaster’s. That is an accomplishment; one wag wrote that after having committed all known sins, John XII had to invent new ones. Unfortunately, no contemporary as eloquent as Liutprand recorded the juicy details of Benedict’s pontificate. The epic tome Liber Gomorrhianus, written by St. Peter Damian within a decade of Benedict’s time, asserted that Benedict IX “feasted on immorality.” The saint depicted the pope as “a demon from hell in the disguise of a priest.” One explanation for Benedict’s opprobrious comportment can be found in an episode from his early years that never received appropriate attention from historians.[36] For his tenth birthday young Theophylact had begged his parents for a brown and white pony with a white tail. A3 and his wife intended to oblige the wishes of their pride and joy, but they weren’t paying close enough attention. They presented him a very attractive brown and white pony, but its tail was brown. A brown tail! Theophylact just lost it. He could not believe how heartless and inconsiderate his parents had been. He decided to withdraw from life forever. He had the servants make him a lunch, brought along some writing instruments to record his innermost feelings about life’s vicissitudes, and climbed to the top of an unused bell tower on the family estate in Tusculum. There he planned to engage in a few hours of sulking. The curious youngster had plenty of time to conduct a minute inspection of the belfry’s environs. Having discovered a loose floorboard in one corner, Theophylact pried it loose and found a sheaf of papers secreted beneath the floorboards. He extracted the package and began to read. To his delight he realized that he had stumbled on an unbelievable treasure – the uncensored diary of Octavian, who became Pope John XII. With rapt attention Theophylact pored over the manuscript and made two incredible discoveries. The first involved Octavian’s father, who, like Theophylact’s father, was named Alberic. He must have really loved his son. He gave him the gift that kept on giving, the papacy itself. The second concerned Pope John’s incredible exploits. Theophylact took out his own quill and parchment and made a list of every scandalous deed to which the Popemaster laid claim. Of course his adolescent mind could not comprehend portions of the work, but that did not inhibit him. He just transcribed whatever his great-uncle had written.The next year his parents did better by Theophylact. On his eleventh birthday they gave little Theo exactly what he had asked for – a pontificate to call his own. After he had been enthroned as Pope Benedict IX, he used the document from the belfry as a checklist to measure the progress of his own reign. The Lateran Palace was frequented by plenty of world-wise cardinals (not to mention the occasional prostitute) who could help the young pontiff with difficult words and phrases.

In at least one respect Benedict failed to measure up to the standard set by John XII. He refused to appoint his horse Senator; that office went to his older brother, Gregory, who must have done a pretty good job because history has essentially ignored him. Besides, the sight of his horse’s brown tail annoyed His Holiness every time that he visited that worthless nag in the pontifical stables.

Benedict IX held the papacy for more than a dozen years. He survived a few assassination attempts – one supposedly foiled by a solar eclipse – and at least one full-fledged coup in 1037. He cultivated a good relationship with the new emperor, Conrad II. In 1039 Conrad was succeeded as King of Germany by Henry III. The pope performed favors for both Conrad and Henry, including the excommunication of a few of their enemies. In exchange both emperors provided him enough support to maintain his grip on Peter’s chair. In 1044 a revolt forced Benedict to flee Rome. The election and installation on January 10, 1045, of the new pope followed the normal process. He took the name Sylvester III. However, Benedict was able to amass a small army, return to Rome, and force Sylvester’s abdication after only fifty days. Sylvester resumed his bishopric in Sabina, and Benedict resumed his pontificate. This was a first; no pope had ever lost his papacy to another legitimate pope – and Sylvester III is definitely on every official list – and then regained it. No pontiff before or since is on the list twice.The still youthful pope’s rule soon reached another turning point. Shortly after scrawling the final checkmark on his list of John XII’s ignominious feats, he got the hots for a young lady. Rome and the girl’s father, however, were not quite ready for a papal marriage. Benedict was willing to abdicate, but the only occupation that he knew was poping. He had taken the tiara at such a young age that he had never even delivered newspapers or flipped burgers. Such a skimpy résumé would preclude landing a coveted job as an investment banker. How would he support his new bride in the style to which they both had grown accustomed?

Benedict’s brainstorm elevated him into a league of his own; he decided to sell the papacy, and a buyer surfaced not far afield. His own godfather, an archpriest named John Gratian, was willing and able to pay Benedict a large quantity of gold or silver.[37] Furthermore, the income from Peter’s Pence – a 1 percent tax levied on English peasants – was allotted to Benedict to assuage his transition to civilian life. John Gratian became Pope Gregory VI. Most Romans were probably happy to have Gregory, a local who seemed sincere about restoring dignity, order, and spirituality back to the papacy, as pope. However, the idea of such a large cash transaction – in which he was not even offered a cut – upset Henry III, King of the Germans. He brought his army back down to Italy in the autumn of 1046 to depose Gregory. He summoned a council at Sutri and ordered Benedict, Sylvester, and Gregory to attend. The council deposed and defrocked Sylvester, and it also forced Gregory to abdicate. Benedict was busy looking at silver patterns with his sweetie, so he could not attend the council. Another synod in Rome deposed him as well. Henry was not even the emperor, but he was allowed to install one of his countrymen as Pope Clement II. Clement immediately crowned Henry as emperor. One hand washes the other. Meanwhile Benedict’s marriage plans somehow came a cropper. Maybe someone sat the prospective bride down and explained to her that a guy who had made a mockery of his vow of chastity was unlikely to remain a faithful husband. Perhaps the young man missed the afternoons lounging on Peter’s throne or the feel of the pallium around his neck. Maybe he just cottoned to the idea of having Roman numerals after his name. Unless someone persuades John Edward to channel him, we may never know. We do know that Pope Clement died under rather suspicious circumstances after only nine and a half months. Benedict then sashayed back into town and forcibly regained stewardship of the Church – for the third time! Some Romans petitioned Emperor Henry to remove Benedict and install still another new pope. He settled on Poppo, a Bavarian who was Bishop of Brixen. Henry faced pressing matters in Germany, so he ordered Boniface, the Margrave of Tuscany, to install Poppo as pope. Boniface, who had actually helped Benedict regain the papacy, told Poppo that he could not dislodge Pope Benedict. Poppo relayed the message to Henry, who was not amused. He insisted that Boniface find a way to make Poppo the pope. Boniface pulled some strings and eventually somehow deposed Benedict and got Poppo installed as Pope Damasus II.“S’ter, what happened to Pope Benedict after that?” One legend related that he persisted in his quest for the papacy for decades. Cormenin credits him with five pontificates![38] Another story insisted that he repented and became a cloistered monk. The latter account is surely preferable, even if it is hard to imagine what kind of abbot would accept a novice with his track record. Whenever a scholar examines a document copied and recopied by monks through the centuries, he/she should contemplate whether it might have passed through the hands of that world-class trickster, Benedict IX, and, if so, what might his contribution be.

The notorious Pope Benedict IX was no flash in the pan. He served as pope for roughly the same amount of time that Franklin D. Roosevelt was president. The period that began with Sergius III and ended with John XII was called “the pornocracy” by a flustered Cardinal Baronius in the sixteenth century. It might make more sense to consider as a unit the entire 141-year period from Sergius III (the second time) to Benedict IX (the last time). Bookended by Theophylacts, it was an era of outrageous papal conduct attributable in large measure to the fact that papal selection was dominated by one or two Roman families and their hired thugs. It was more than an unpleasant footnote to Church history. A little more than 10 percent of the names on the official list and over 7 percent of the entire Christian era fall into this period in which, excepting only one or two short pontificates, the popes were scarcely even Christians. The most puzzling question is how an entire millennium could transpire before the Church took seriously the idea of establishing rules of papal succession.I have to wonder what would have happened if, during my time in Sr. Mary Immaculata’s class, I had stumbled across a book about the conduct of the popes of the tenth and eleventh centuries. What would S’ter have done after she read my book report? Two ugly pictures emerge: One involves a hastily called meeting with my parents featuring tight-lipped faces. The other is even worse; not even a smart-alec wants to see a nun in tears.

[1] The pontiff would have received much more sympathy from the boys in our class. The code of silence was sacred to us, like the omertà to la‘ndrangheta in Calabria. Anyone who broke the code by ratting out on a schoolmate was labeled a fink and was subject to the ultimate punishment, depantsing.

[2] A different explanation was offered in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. King Arthur postulated that all witches were made of wood and therefore weighed exactly as much as ducks. Thus, ducks and witches are equally buoyant.

[3] Cormenin, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 224.

[4] Cormenin, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 225.

[5] This is not a misprint. The twentieth-century John XXIII was only the twenty-first pope named John. The tenth-century John XVI has always been considered a hapless antipope. There was also no Pope John XX. In the fifteenth century an antipope named John XXIII was considered legitimate by most Christians at the time. However, he was pressured into calling the Council of Constance, which deposed him. In 1958 Angelo Roncalli named himself John XXIII in part to clarify that his namesake was an antipope.

[6] Adrian had reportedly turned down the papacy on two previous occasions. He had a wife named Stephania and a daughter, both of whom were brutally murdered during his papacy.

[7] Has anyone else in history ever been convicted of coveting an appointment to Bulgaria?

[8] The origins of this controversy are detailed in the next chapter.

[9] The heirs of Charlemagne’s bloodline.

[10] Cormenin claims that “most reliable historians” think that he was poisoned by an agent of his successor. Op. cit., Vol I, p. 373. Life insurance for ninth-century popes was underwritten at a rate ordinarily reserved for tiger handlers and barnstorming stunt pilots.

[11] The other co-judge was the future Pope Sergius III.

[12] Pope Romanus was probably deposed, but the record is not certain.

[13] Matthew 18:22.

[14] Chamberlin might be a little too facile with words like “endless” and “countless.” Rome had been sacked only a few times. The resulting structural damage was not traumatic, at least not in comparison with what was to come.

[15] E. R. Chamberlin, The Bad Popes, Barnes and Noble Press, 2003, p. 5.

[16] Gibbon, for example, mistakenly attributed some of the mother’s actions to the daughter.

[17] Oh, don’t be so judgmental; even in the twenty-first century the age of consent in Hawaii is only fourteen.

[18] Invading peoples already mentioned include the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Huns, Vandals, Lombards, and Franks. The Saracens were already moving up the boot from their colony in Sicily, and in the eleventh century a contingent from Normandy, descendants of Vikings, would mount an extremely successful invasion. As William was conquering England, Count Roger marched through Sicily and southern Italy.

[19] A different Hugh of Provence was the first person known to have worn eyeglasses.

[20] The name means “elf power.”

[21] The Latin word “princeps” means “first head” or leader. There is no connotation of being secondary to a king.

[22] Cormenin, op.cit., Vol. I, p. 292.

[23] Why he would choose the letter J, which is not used in either Latin (Ioannes) or Italian (Giovanni) is never explained in Liutprand’s chronicles.

[24] If Sr. Mary Immaculata had taught us about this episode, I would have asked whether the episcopal youngster’s mother allowed him to come to the Lateran Palace for sleepovers.

[25] There is some confusion about this. Cormenin reports the death in the Lateran of a woman with the same name in the juvenile pope’s first term.

[26] Peter De Rosa has slandered Pope Benedict V. Although he has the right date for Benedict, he must have confused him with someone else, possibly Boniface VII, who is considered an antipope. Incidentally, the “pious church historian” named Gerbert mentioned by De Rosa is better known as Pope Sylvester II. Vicars of Christ, Crown Publishers, Inc., 1988, pp. 47-8. A great deal of controversial material in this book is difficult to verify because the author provided no useful footnotes like this one.

[27] Rendina, op. cit., p. 335.

[28] Sir Roger Greisley, The Life and Pontificate of Gregory VII, London, 1982, p. 6.

[30] Currently the statue is in the Palazzo dei Conservatori on Capitoline Hill. A replica stands in the piazza there.

[31] John Fletcher Hurst, History of the Christian Church, Eaton & Mains, 1897, Vol. 1, p. 730.

[32] Allegedly the two hoped to emulate the supposedly close relationship Emperor Constantine and Sylvester I.

[33] Arithmetic with Roman numerals is quite difficult. Fibonacci’s book promoting the use of Arabic numerals was not published until 1202.

[34] This is not a joke. It is a serious offer available from the James Randi Educational Foundation (www.randi.org).

[35] Sr. Mary Immaculata is offering a holy card of St. Wilgefortis to the reader who produces the most complete and accurate diagram of the Theophylact/Crescentius family tree. All the information that you need is in this chapter.

[36] In fact, not a single reference to this episode can be found in the historical literature.

[37] Did Vince McMahon study medieval papal history? In 1988 Andre the Giant defeated Hulk Hogan for the championship of the World Wrestling Federation. He then sold the belt to his manager, Ted DiBiase, the Million Dollar Man. DiBiase had assisted Andre by kidnapping the assigned referee, Dave Hebner, and substituting his twin brother Earl, who was identifiable on replays by the wad of C notes spilling out of his back pocket as he counted Hogan out.

[38] Cormenin, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 348. This account differs from others in many particulars.

| |

| |

Bankable Bar Bets

$ Pope Paschal I shielded two of his servants accused of murder on the grounds that their victims had been guilty of treacherous conduct.

$ Pope Adrian II’s wife and daughter were murdered during his pontificate.

$ Pope Formosus had been excommunicated while he was still a bishop.

$ Pope Boniface VI had been defrocked twice. He apparently had never been reinstated at the time that he became pope.

$ Pope Stephen VI (VII) exhumed Pope Formosus’s corpse, dressed it in papal vestments, and put it on trial. After he found it guilty, he stripped off the vestments, broke three fingers off of the cadaver, and ordered the remains pitched in the river.

$ Pope Stephen VI (VII) declared that all priests and bishops installed by Formosus were invalid. He evidently forgot that he himself had been made a bishop by Formosus.

$ Christopher deposed and incarcerated Pope Leo V and then named himself pope.

$ Pope Sergius III, who served as co-judge at the Cadaver Synod, was elected pope twice. The first time he was run out of town before his papacy even started.

$ Pope Sergius III had a fifteen-year-old mistress named Marozia. She gave birth to a son who became Pope John XI.

$ The Normans conquered Sicily and southern Italy in the eleventh century. They were descended from Vikings and became Christians in France.

$ Pope John XI performed the ceremony for his own mother’s wedding.

$ Marozia became Senatrix and Patricia of Rome. She personally selected several popes, including her son. Another son captured her and threw her in prison

$ Pope Stephen VIII (IX) had his nose cut off.

$ Pope John XII was at most eighteen when he became pope.

$ Pope John XII turned the Lateran Palace into a brothel. This was by no means the worst of his crimes.

$ Pope John XII appointed his horse as Senator of Rome.

$ Donus II was included for many centuries in the official list of popes. He never existed.

$ The antipope Boniface VII was elected in a canonical manner and served as the uncontested Bishop of Rome for two rather extended periods. However, he is not considered a legitimate pope.

$ John XVI was also an antipope. The emperor cut off his nose, ears, and tongue. He also gouged out his eyes, but the poor man lived for fifteen more years.

$ Pope Benedict IX was very young. Some say he was only eleven-years old.

$ Benedict IX became pope three times.

$ Benedict IX sold the papacy to his godfather so that he could get married.