Chapter 12: Taking French Lessons

The Pope Names a Champion

Chapter 10 left Sinibaldo de Fieschi, formerly Emperor Frederick II’s close associate, exiled in Lyons. Ever since Fieschi became Pope Innocent IV in 1243, he had single-mindedly focused on terminating Frederick’s reign, with little effect. After his nemesis died in 1250, the pope returned to Rome. “When everything was ready for their departure, Brother Hugh, a cardinal, on behalf of the pope took leave of the citizens of Lyons … ‘My friends,’ said he, ‘since we arrived in this city we have done much good and largely bestowed alms; for when we first came here, we found three or four brothels, and now at our departure we leave behind us only one; but that extends from the eastern gate of the city to the western one.’”[1]Frederick had willed his kingdoms to two of his sons, Conrad IV and Manfred. Conrad eventually solidified his authority in Italy and Germany. Before his death in 1254 he inexplicably appointed the pope guardian of his two-year-old son, Conrad (known as Conradin or Conradino). Pope Innocent felt confident enough in this new role in loco parentis to claim the two Sicilies as papal states. Before his audacious land grab could be tested, however, he followed Conrad IV to the grave. The next pope, Alexander IV, boldly offered the Hohenstaufen lands in Germany to the King of Castile, but nothing came of it.

In 1527 Pope Alexander, who was, like all other pontiffs, elected Bishop of Rome, packed up his vestments and moved sixty-seven miles north to Viterbo. Viterbo already had a bishop, but the pope took over his headquarters and transformed it into a papal palace. The popes resided ther from 1257 to 1281.

In 1258 Manfred arranged to be named Conradin’s regent in Sicily. He then won several battles, culminating in the renowned triumph at Montaperto[2] in support of the Ghibellines of Siena over their hated rivals, the Florentine Guelphs. The pope at the time was Urban IV. Phase one of his response to Manfred’s success was the familiar volley of excommunications. In 1262 His Holiness, fearing lest Manfred stir up as much trouble for the papacy as his father had, happened upon this card in his Rolodex:In 1264 another Frenchman, Gui Faucoi le Gros, succeeded Pope Urban and became Pope Clement IV.[3] He promised to elevate Charles’s quest to the level of a crusade. Even so, Charles could muster only one thousand knights (sans horses!). Their long slow march gave Charles time to integrate Italian indulgence-seekers into his force. In January of 1266 he finally confronted Manfred northeast of Naples near Benevento. Some of Manfred’s barons deserted him, his remaining army was routed, and Manfred himself was slain. Even though Benevento was a papal town, Charles’s army celebrated with a bloody sack; for more than a week they conducted a wholesale slaughter of its inhabitants. The behavior of his crusaders shocked Pope Clement, but he took no action.

In 1084 Rome had been sacked after Pope Gregory VII granted Robert Guiscard carte blanche. Christian Constantinople had been burned after Pope Innocent III lost control of the Fourth Crusade. The same trick backfired on Pope Clement in Benevento. From this point on, however, most popes remembered the lesson. The white card generally remained sequestered up their capacious sleeves.After Pope Clement crowned him King of the Two Sicilies, Charles enjoyed a short honeymoon period with his new subjects. Mezzogiorno residents were so eager to rid themselves of each tyrannical ruler that they tended to overlook his successor’s shortcomings. Soon, however, the high taxes that Charles imposed, his draconian collection methods, and his disdain for his subjects led them to yearn for the good old days of the Hohenstaufens. Evidently they had no aphorism equivalent to “Better the devil that you know …”

In 1267 fifteen-year-old Conradin led an army into Italy to reclaim his kingdom. Pope Clement IV welcomed them with a blanket excommunication. King Charles defeated the young man’s force at Tagliacozzo in Abruzzo east of Rome and captured many of Conradin’s men. He then ordered the prisoners’ feet amputated, the helpless captives carted into a nearby building, and the structure set on fire. Conradin escaped this horrid fate, but he too was soon captured. Interpretations of the Geneva Convention prevalent in the thirteenth century evidently permitted dismembering prisoners and then burning them alive. However, executing a captured leader was a deplorable violation of the laws of chivalry. Moreover, it was poor public relations to kill a handsome and popular teenager like Conradin – supposedly the pope’s ward! – before his junior prom. Nevertheless, Pope Clement allegedly sent King Charles a terse instruction: “Vita Conradini, mors Caroli; vita Caroli, mors Conradini.” Charles understood without even consulting his Collins Gem Latin Dictionary. His lawyers proclaimed that Conradin was guilty of trespassing as well as treason. Charles’s judges convicted him. Europeans were shocked and scandalized when Conradin was beheaded. At that point in Sicily Charles controlled only the cities of Palermo and Messina; the rest of the island had already revolted. Charles took measures to consolidate his power and then joined King Louis IX in Tunis on the abortive Eighth Crusade. He never got close to Jerusalem, and he lost his beloved brother. However, Charles’s lucrative deal with the emir and his dabbling in the scavenging business left his kingdom solvent for the first time in his reign. The king invested his surplus in an attempt to expand his holdings into an empire. He made Naples his capital. After successfully attacking Albania he declared himself its king, but he could not hold it. By 1281 the Byzantines had recovered most of Charles’s territories on the eastern side of the Adriatic. In the fateful spring of 1282 Charles began to prepare a counter-attack. He had designs on Constantinople itself.The Sicilian Vespers

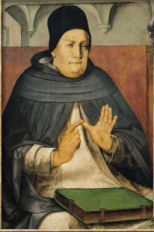

King Charles never enjoyed a high Q score in Sicily. He ruled with an iron hand. His disdain for the locals had led him to import hundreds of Frenchmen to administer his territories. He awarded fiefs to Frenchmen and Provençals. He insisted on French as the official language of the government. His appetite for foreign conquests necessitated oppressively high taxes. He failed to squelch outlandish rumors,[4] including one that he had poisoned St. Thomas Aquinas, who lived and taught in Naples. On March 30, 1282, after the evening service (Vespers) at a church outside of Palermo a row erupted between a squad of French soldiers and some locals. Well-armed[5] Sicilians appeared out of nowhere and killed all the Frenchmen. Church bells tolled throughout the city, and the previously passive natives took to the streets as one and slaughtered all the French, even those French by marriage. Women, monks, and priests were not exempted. By sunrise a couple of thousand people had been slain. The movement then spread to other towns in Sicily, and the number of dead reached four thousand. In Messina, Charles’s fleet was set afire. The king was in Naples; by the time that anyone apprised him of the disastrous state of affairs, Sicily was lost to him for good. He tried to retake Messina, but he abandoned the project when he learned that King Peter of Aragon had made port on the west coast of Sicily to a warm greeting from the citizens of Palermo. Peter and Charles negotiated an unusual compact to resolve their dispute over the island. Each agreed to select one hundred knights to compete in a battle royal, winner take the kingdom. This approach has a relatively civilized sound, but Pope Martin IV forbade it. Neither king heeded the pontiff. Even the threat of excommunication failed; King Peter was at that point already excommunicated, and no one could ever tell King Charles what to do. The pay-per-view rights were licensed to Sky TV, and the event was scheduled for June 1, 1283, in Bordeaux, France. A site 856 miles from Palermo might seem inconvenient, but nothing refreshes the spirit after a battle royal like a chalice of Bordeaux Supérieur. Peter was a morning person; he had his stalwarts up and stretching before dawn. Having carefully positioned themselves so that the morning rays would be in their opponents eyes, they took the field shortly after the early-born rosy-fingered dawn appeared. No one appeared to face them. Peter cautioned them to hold formation for the entire ten minutes accorded to a full professor. Then he had his trumpeters proclaim a great triumph, and they all departed to celebrate. Charles’s men, in contrast, had partied all night. They arrived at the battlefield shortly after their midday siesta, found it empty, cursed their opponents as dogs and cowards, and, satisfied that they had performed with honor and distinction, departed in the opposite direction. So much for the battle royal. King Charles must have belonged to the school of philosophers who savor life’s journeys more than achieving the destinations. It took him a year to wend his way back to southern Italy. During his absence the revolts had spread to the mainland. His son and namesake, whom he had left in charge, had made a mess of things and was even taken prisoner. Charles continued the struggle, but he never fully regained power.One noteworthy legacy of Charles’s rule was the Kingdom of Naples’s permanent divorce from Sicily. Perhaps his most remarkable achievement was that he lived and ruled in Italy for twenty years, and evidently no pope ever excommunicated him. There was a reason for that.

Charles’s Popes

The next conclave produced an obscure Portuguese named Petrus Juliani. Arithmetic, which is admittedly more difficult with Roman numerals, was not his forte. According to his ciphering, XIX + I = XXI. He picked the name John XXI even though no pope had ever selected John XX. He reigned for about a year. He had a new room constructed for himself in the Papal Palace in Viterbo so that he could conduct medical research in private. One day the roof collapsed and killed him. At his death there were only VII cardinals.

In 1277 Pope John was followed by Nicholas III, a member of the powerful Orsini family. He devoted much of his short papacy to spreading wealth and benefices among his relatives and amassing a personal fortune from his cut of property confiscated by the Inquisition. He was never Charles’s stooge; in fact he conspired with Peter of Aragon to overthrow Charles in Sicily. Dante conversed with him in the eighth circle of hell.King Charles learned a valuable lesson from Nicholas’s pontificate. In 1281 Charles hand-picked Simon de Brie and brought his army to Viterbo, the site of the conclave. To assure that the cardinals got the message, Charles imprisoned two of them. Their fellows were wise enough to elect de Brie with the name Martin IV. His failing was not arithmetic, but spelling. Even though he was only the second Pope Martin, he determined his numerical designation by counting the two early popes named Marinus as Martinus (Martin). Thus, there is a Pope Martin I and Martin IV, but no Martin II or Martin III. If the world has always been run by C students, why not the Church? Pope Martin named King Charles Senator of Rome. In support of Charles’s Balkan claims he excommunicated the Byzantine Emperor, Michael VIII Palaeologus. Any chance of reconciliation with the Greek Church was probably obliterated by this act. Pope Martin also excommunicated Peter of Aragon and even initiated a crusade against him. As a cardinal Pope Martin had attended the roofless conclave of Viterbo, where he had personally witnessed Guido of Montfort’s “mass murder” of Henry of Cornwall. Nevertheless, Marin evidently appreciated something in Guido’s character and appointed him commander-in-chief of the papal army in 1283. “At least Guido was decisive and efficient.”[10]King Charles died on January 7, 1285. Pope Martin lasted until March of the same year.[11] By then Charles’s popes had appointed enough French cardinals to elect the invalid Giacomo Savelli as Pope Honorius IV. He steadfastly supported Charles’s heirs against the house of Aragon. The pontiff was so loyal that he refused to allow Charles of Salerno, the ne’er-do-well son of Charles of Anjou, to abandon his claim to Sicily. Pope Honorius also excommunicated a few Spanish princes for good measure.

At Honorius’s death in 1287, the French and Italians cardinals were equally powerful. They disputed for ten months,[12] finally settling on a Franciscan monk named Girolamo Masci, who became Pope Nicholas IV. His peculiar interpretation of St. Francis’s rules was exemplified by his lobbying of the French government to attack Sicily in support of Charles of Salerno’s claim, even though Charles obviously lacked interest in the island.

Let’s Try Another Saint

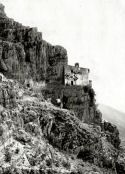

When Pope Nicholas IV expired in 1292, eleven Italians and two Frenchmen met in conclave in Perugia. The Italians formed three factions – the Orsinis, the Colonnas, and those who owed their careers to the Anjous. After twenty-seven long months of deadlock, a truly astounding chain of events occurred. A letter signed by a hermit, the Benedictine monk Peter da Morrone, arrived.[13] For fifty-three years Morrone had shunned contact with his species. At first he resided in a cave on Mt. Morrone. Then he moved to Mt. Maelli, where he adopted the lifestyle of his idol, John the Baptist. He maintained his skeletal figure by fasting six days a week. Three times a year he subsisted on nothing but bread and water for forty days. A group of fanatical monks emulated his regimen and formed a sub-order of the Benedictines. In 1284 Morrone, already considered either the holiest or the craziest living human, abandoned his leadership position for even greater solitude.

Celestine flooded the College of Cardinals with appointments of Frenchmen and Neapolitans. King Charles helpfully supplied him with suitable names. Cardinal-packing seems like a rather pedestrian trick, but no previous pontiff had dared attempt it. King Charles apparently invented the effect, but many future pontiffs – even John Paul II – made profitable use of it.

Aside from his chains, his rags, his donkey, and his stench, Celestine had avoided possessions throughout his life. He seemed unable to grasp the value of anything and was hopeless at record-keeping. He awarded benefices to almost anyone who requested them, and he once gave the same one to three different people. He irritated the cardinals by enforcing rules that restricted their lifestyle. The last straw was when he began giving away the papal treasury to the poor.Since Nicholas the Great’s pontificate in the ninth century, the only popes canonized[15] as saints were Leo IX, who may have benefited from comparison to the long list of deplorable popes preceding him, and Gregory VII, the mainstay of the reform movement whose pontificate ended in disgrace and exile after his complicity in the sack of Rome. Two out of eighty-seven is not a great record for a profession with appellations like “Holiness” and “the Vicar of Christ.” Nevertheless, five months of another saintly pontiff was as much rectitude as the cardinals could possibly tolerate. They pined for the bygone days of ruthless political maneuvering, nepotism, and arrogance in the papacy. They got their wish.

“Just Make Your Mark Here, Your Holiness”

Cardinal Benedict Caetani (often written Gaetani) took full advantage of Celestine’s short papacy. Not only did he ingratiate himself with all competing factions among the cardinals – the Colonnas, the Orsinis, the French, and the Neapolitans. He also concocted a tricky solution to the problem of the loose cannon in Castel Nuovo: The pope would just resign. There was little precedent for orderly papal abdication. The records are spotty, but only one pope certainly resigned voluntarily. Benedict IX, in order to facilitate his impending marriage, sold the papacy in 1045 to John Gratian; when his main squeeze dumped him a short time later, Benedict successfully reclaimed the papacy. Despite this shaky legal basis, Caetani, widely acknowledged as a legal scholar extraordinaire, cobbled together a canonical justification for papal abdication. His approach seemed to pass the smell test, although some might protest that his fellow cardinals were not particularly renowned for their olfactory sensitivity. Along with a letter of resignation, Cardinal Caetani and a group of lawyers thoughtfully brought Pope Celestine a bull that they had composed to validate the concept of papal abdication. Shortly thereafter they emerged with his approval.Celestine detested his five-month pontificate. He may have been about to resign when Caetani presented him a tenable out. Astounding coincidences sometimes occur.[16] On the other hand, a few cynics in Sr. Mary Immaculatas class might have noticed that the man who emerged with all the marbles was the event’s architect, Benedict Caetani himself. The cardinals were so impressed with his handling of the case of the saintly pontiff that they rapidly elected him pope. The legend, which would have vehemently been denied by the nuns, has persisted through the ages that Caetani tricked the naïve pope into resigning.

They used the following trick to determine Celestine to abandon the pontificate. Having been informed by a chamberlain that the pope was frequently in the habit of shutting himself up in a secret chapel … the cardinal (Caetani) caused the wall to be pierced behind the lace occupied by the crucifix, and introduced, into the opening a speaking trumpet, which communicated with a chamber of the upper story: then, during the silence of the night, when the pontiff had retired to his chapel to pray, he called out to him in a terrible voice : “Celestine! Celestine! cast aside the burden of the papacy – it is a charge beyond thy strength.”[17]

Caetani selected the name Boniface VIII on Christmas Eve, 1294. Boniface VII had been taken by Franco Ferrucci in 974. He ruled a while, fled to Constantinople, and then returned to power as the unchallenged pope a second time. He had been labeled an antipope, but Caetani, Europe’s foremost canonical scholar, evidently thought otherwise.

Nobody worried about Boniface VIII turning excessively saintly. His first trick was to make his predecessor disappear. He tossed the aged monk, who probably sought nothing more than his cave, into prison. Pope Boniface justified this preventive detention as necessary to forestall popular riots in Celestine’s favor. Never did he claim that Celestine had committed a crime or even posed a direct political threat. Boniface quickly reversed most of Celestine’s papal decrees. The Church’s administrative condition was sorry enough that wiping the slate clean was a popular move. Morrone had survived for decades in his squalid cave in the mountains, but he passed away after only two years in Fumone Castle.The Family Crusade

Religious orders that benefited from Pope Celestine’s largesse protested Boniface’s harsh treatment of his predecessor. One powerful Roman faction joined them. The Colonna family’s two cardinals, Giacomo and Pietro, loudly denounced Pope Celestine’s suspicious resignation and imprisonment. The family soon had much more to complain about. Boniface, like most popes, directed benefices and other goodies toward his own relatives. He also favored the Colonnas’ archrivals, the Orsinis, with plum appointments.

In 1297 the dispute reached a head. The Holy Father had arranged a large shipment of papal gold for the purchase of a fiefdom for one of his nephews. Stefano Colonna intercepted it Butch Cassidy-style and absconded with the bullion. Pope Boniface not only demanded Stefano’s surrender and the return of the missing gold; he also deployed troops in the Colonnas’ territory. The family agreed to turn over Stefano and the bullion, but it drew the line at military occupation. The pope excommunicated first the cardinals and then the rest of the Colonna family. His next moves included the following:• He ordered the papal army to seize all of the Colonnas’ property.

• All crops were destroyed.

• The people working the land were sold into slavery.

• A crusade, complete with indulgences, was called against the Colonnas – all of Christendom against one family.

The Colonnas sought refuge in Palestrina, an ancient fortified town considered impervious to attack. Their cardinals begged for forgiveness, and the two sides negotiated terms of surrender in which the Colonnas were led to believe that, if they were suitably penitent, the status quo ante would be restored. Instead, the pope ordered the town of Palestrina leveled and its inhabitants killed. The number of dead has been estimated at six thousand. Salt was spread over the ground. All possessions of the Colonna family were given away, mostly to the pope’s relatives. The Colonnas who survived fled to foreign lands.Twenty-first century sensibilities find quite a few papal acts unconscionable. Still, no previous pontiff had ever directly ordered this kind of massacre.

Jubilee

Nobody in Sr. Mary Immaculata’s class knew about any Colonnas except for Jerry, Bob Hope’s mustachioed sidekick. We certainly never learned that a Vicar of Christ ordered the slaughter of a town populated by practicing Christians. We did, however learn about one event associated with this pontiff, the wonderful tradition of the Holy Year of Jubilee. On December 31, 1299, Rome’s plight seemed unimaginably dire. The population had reached an incredible nadir; the former center of civilization was home to only twenty thousand or so souls. However, the beginning of the fourteenth century sparked a turnaround. Rome suddenly became the hot destination for Christian pilgrimages; for some reason Europeans decided that the year with two zeroes at the end marked a good time to visit the sacred sites there. Pope Boniface did not initiate this fad, but he gets star billing for cleverly maximizing the effect. On February 22, 1300, he issued a papal bull, “Antiquorum Fida Relatio.” It declared 1300 a Jubilee Year and offered a plenary indulgence to anyone who had missed out on the crusade against the Colonnas. All that was required was a visit to St. Peter’s Basilica and St. Paul’s Outside the Walls fifteen times (thirty times for residents) on consecutive days during the year. What a great idea! People came to the Eternal City by the tens of thousands.[18] The monks reportedly needed rakes to gather in the coins donated at the sacred sites. One of the pilgrims was Dante Alighieri.The Wit and Wisdom of Pope Boniface

Pope Boniface VIII was one of the first popes to patronize the arts. Surviving are numerous statues and paintings of his likeness – a large, stern figure, with prominent features. The gap between his teeth reportedly caused spittle to erupt from his mouth during his orations. He was fifty-nine when he took the throne and sixty-eight when he died.[19]Numerous popes had mistresses. Boniface allegedly kept both a married woman and her daughter at the same time. One envisions him doing mom on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday and sis on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. On the seventh day, like the Lord, he probably rested. He has been quoted as saying, “Sex and the satisfaction of natural drives is as little a sin as washing one’s hands.”

Probably no Roman since Nero could match Pope Boniface’s arrogance. While overseeing the inundation of pilgrims in 1300, he was overheard chanting, “I am pontiff; I am Caesar.” Outside of his circle of family and friends in Anagni, he may have been the least popular pope ever or at least the most despised pope who was never run out of town. The Spanish doctor who saved Boniface’s life was considered the second most hated man in Rome.After Pope Boniface’s death, King Philip the Fair of France prosecuted him for the murder of Pope Celestine V[20] and other heinous crimes. This was not another Cadaver Synod; Boniface’s corpse remained entombed. The pope was never even convicted of anything; the trial reached no conclusion about his culpability. Nevertheless, much interesting testimony was elicited. Here are some samples of quotations attributed to His Holiness:

• The Christian religion is a human invention like the faith of the Jews and the Arabs.

• The dead will rise just as little as my horse, which died yesterday.

• Mary, when she bore Christ, was just as little a virgin as my own mother when she gave birth to me.

• Paradise and hell only exist on earth; the healthy, rich, and happy people live in the earthly paradise; the poor and the sick are in the earthly hell.

• The world will exist forever; only we do not.

• Any religion, and especially Christianity, does not only contain some truth, but also many errors. The long list of Christian untruth includes the trinity, the virgin birth, the godly nature of Jesus, the eucharistic transformation of bread and wine into the body of Christ, and the resurrection of the dead.

• I care no more for another life than for a bean.

• The gospel teaches more falsehoods than truths: the delivery of the Virgin is absurd; the incarnation of the Son of God is ridiculous; transubstantiation is a folly.

• Religions are created by the ambitious to deceive men.

• We must sell in the church all that the simple wish to buy.[21]

Boniface VIII is justly famous for his bull, “Unam sanctam,” which specified the rationale for Christian deference to the pope. It concluded that “outside of the Church there is no salvation or remission of sins … Therefore, We declare, affirm, and define as a truth necessary for salvation that every human being [emphasis added] is subject to the Roman pontiff.”

The Slap

Boniface VIII bickered with practically everyone; he considered himself every man’s master, and he expected everyone to bow to his will. He conducted a long bitter quarrel with King Philip the Fair of France. Sciarra Colonna, who had narrowly escaped the massacre at Palestrina, joined Philip’s court. Revenge may be a dish best served cold, but Sciarra’s hatred of the pope never got below scalding. In 1303 both the weather and the politics grew uncomfortably hot in Rome. Boniface retired to his ornate palazzo in his home town of Anagni. He planned to work on a bull excommunicating King Philip. Meanwhile Sciarra Colonna and William of Nogaret, one of King Philip’s councilors, had reached Rome with a sizeable force. Only seventy-two kilometers separated them from Anagni. They marched. The arrival of the hostile troops in Anagni inspired most of Pope Boniface’s court to abandon him. Only four or five cardinals accompanied the pontiff as he sat majestically on his throne beneath his two-tiered tiara. When Nogaret and Sciarra confronted the pope, he denounced them as heretics and challenged them to behead him. One chronicler claimed that Sciarra slapped the pope with his gauntlet. Much has been made of this, because evidently striking a pontiff with an article of clothing was considered much more scandalous than merely sacking a city and snuffing thousands of lives. Even Dante was shocked by the pope’s reported mistreatment.The confrontation never went much beyond the face-to-face exchange and the looting of the pope’s belongings.[22] The cardinals roused the citizens of Anagni, who, after all, had reaped enormous profits from Pope Boniface’s attentions. They came to the rescue of their homeboy pontiff and captured Nogaret.

The encounter had an unexpected effect on the pope. He forgave Nogaret and released him, the only known occasion in which he exhibited any semblance of mercy. Then, in the course of just thirty days, the defiant dynamo that was Boniface VIII withered away and died. Rumors of the cause of death – that he continually beat his head against the wall in frustration or gnawed his own flesh – abounded. However, his corpse was exhumed three hundred years later, and it showed no signs of physical trauma.

Pope Boniface left behind many enemies. Loyal Christians prayed that the papacy could move on. Some just wanted it to move.

[1] Matthew Paris, English History from 1235 to 1273, translated by J.A. Giles, Henry G. Bohn, 1853, p. 443.

[2] This was Siena’s only significant victory over Florence until February 20, 2005, when A.C. Siena upset the Viola of Fiorentina 1-0.

[3] Clement IV was the fifth consecutive fourth: Celestine, Innocent, Alexander, and Urban were the others. Italians called Clement “Guido il Grosso,” Guido the Fat.

[4] Spread by, among others, Dante Alighieri.

[5] There is a every chance that the revolt was underwritten by both the Byzantines and King Peter of Aragon, who had established a claim to the kingdom of Sicily by marrying Manfred’s daughter.

[6] They also brought the corpse of the saintly third brother, King Louis IX!

[7] Martin, op. cit., p. 165. Fr. Martin mistakenly identified the river as the Po, which is well north of Florence.

[8] A man named Vicedomino de Vicedominis, the cardinal-nephew of Pope Gregory X, was reportedly elected as Pope Gregory XI, but he died the next morning.

[9] The North British Review, December 1866, p. 166.

[10] Martin, op. cit., p. 161.

[11] Dante consigned the pontiff to Purgatory. Charles was seen singing outside Purgatory’s gate.

[12] “The conclave that ultimately elected Nicholas … happened in the middle of the hottest season of the year. Their eminences, unable to agree in an election, remained until six of their number died of malaria fever, and many of the survivors were very ill.” T. Adolphus Trollope, The Papal Conclaves as They Were and as They Are, Chapman and Hall, 1876, p. 84.

[13] Italian writers have long claimed that Charles II, the King of Naples, tricked Peter into writing the letter. Rendina, op. cit., p. 501.

[14] Cormenin, op. cit., Vol. 2, p. 28.

[15] Pope Gregory X is considered a saint in some places in Italy, but he was never canonized.

[16] For example, National Public Radio assigned the reporter Libby Lewis to cover the trial of I. Lewis Libby.

[17] Cormenin, op. cit., p. 29

[18] But not a single ruling prince or head of state!

[19] For some reason De Rosa claimed that Boniface was eighty-six when he died. The amount of erroneous information contained in books on the papacy is staggering. Who proofreads these things?

[20] The Associated Press recently picked up the story of an Italian monk who reported finding a hole in the forehead of Celestine V’s skull.

[21] A detailed account of the testimony of the twenty-three witnesses can be found in Henry Hart Milman, History of Latin Christianity, Murray, 1855, vol. VII, pp. 287-294.

[22] “The palaces of the Pope and of his nephew were plundered; so vast was the wealth, that the annual revenues of all the kings in the world would not have been equal to the treasures found and carried off by Sciarra’s freebooting soldiers.” Milman, op. cit., vol. VII, p. 152.

| |

| |

Bankable Bar Bets

$ Pope Urban IV commissioned Charles of Anjou to drive Manfred Hohenstaufen out of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Pope Clement IV elevated Charles’s mission to the level of a crusade. After the first battle near the papal city of Benevento, Charles’s men sacked the pope’s town and slaughtered its inhabitants.

$ The thirteenth century featured five consecutive popes who were IV’s.

$ After one victory the soldiers of Charles of Anjou cut off the feet of the men whom they had captured, stacked the captives in a building, and set it on fire.

$ Conradin was only sixteen when Charles of Anjou executed him.

$ In the long conclave that began in Viterbo in 1268, Guido of Montfort murdered Henry of Cornwall during mass in full view of most of the cardinals.

$ Charles of Anjou was present in Viterbo for the conclave. So was the corpse of his brother St. Louis IX of France.

$ The cardinals wore out their welcome in Viterbo. After more than two years of indecision, local carpenters removed the roof from the building in which the cardinals convened.

$ Pope Gregory X put Florence under interdict. At one point he removed the interdict, walked through town, and then restored the interdict after departing the city.

$ Pope Adrian V was never ordained a priest.

$ There is a Pope John XIX and a Pope John XXI, but no XX.

$ In the conclave of 1287-1288 six cardinals reportedly died.

$ There is a Pope Martin I and a Pope Martin IV, but no II or III.

$ Pope Celestine V wore rags and iron chains around his body as a gesture of self-abasement.

$ Pope Boniface VIII declared a crusade against the Colonna family.

$ Pope Boniface VIII ordered the destruction of Palestrina and the killing of its six thousand inhabitants.

$ Pope Boniface VIII came up with the idea of granting indulgences to pilgrims during “Jubilee Years.” In 1300 priests reportedly used rakes to gather in all the coins.

$ Many shockingly heretical remarks have been attributed to Pope Boniface VIII.

$ Sciarra Colonna allegedly slapped Pope Boniface VIII. The pope died only a month after the confrontation.