Breakfast was the fare that we had grown accustomed to eating at European hotels. Sue and I consumed ours together at about 7:30.

At 8:45 the group assembled in Piazza Rilussa for the Ghetto walk. Sue decided to save her knees by passing on the guided walk. She felt bad about abandoning Charlotte so early in the tour, but she hoped to be able to meet up with the rest of us at the Capitoline Museum. I did not expect to see her when we arrived there, but Sue was always full of surprises.

Judy seemed to have developed a rather severe cough. I hoped that she recovered soon, and just as fervently I hoped that she did not pass it on to me or (more likely) Sue. I had been sick surprisingly few times in my entire adult life. Missing a day or two of work would be one thing, but an illness could ruin the rest of the trip.

What ho? Jeff was wearing flip-flops that clearly displayed ten (not that I counted) teal-colored toenails. No one said anything, at least not in my presence.We met our guide, Francesca Caruso, on the Ponte Cestio, the ancient stone bridge that for centuries had connected Trastevere with Isola Tiberina, the island in the Tiber. Rainer had told us that Francesca was immediately recognizable because she had a sort of halo about her. Maybe Kurlian photography would reveal it; the shots from my Canon did not. I did notice an engaging smile, blonde hair, and dimples.

Also waiting on the bridge was Ben Cameron, one of Rick Steves’ guides and the co-author of the guidebook that had been weighing down my backpack for several days. Since the Benino that Sue had introduced to the group was absent from this excursion, Rainer suggested that we address Ben as Benino. I don't know; Ben was a big guy. Benone would seem to be more appropriate.

Francesca told us that her mother was an American, and her father was a Roman. She grew up speaking both English and Italian. I don't know about her Italian, but her English was impeccable, and she definitely sounded American, not British. We all wore earpieces, and she spoke into a microphone that she wore Madonna-style. She was a treasure trove of interesting information, and she was not bashful about sharing it. I filled up page after page in my spiral notebook. She went at just the right pace for me. I undoubtedly missed a little, but I definitely absorbed a lot.Rome, we learned, was the world’s first megalopolis. Up to 1.5 million people lived in the city in the second century. By the tenth century or so it was down to about twenty thousand. Such a collapse was just unimaginable. Rome must have resembled a ghost town in the Middle Ages.

Tiber island was critical to Rome’s development as a commercial center. It was easier to build and maintain two small bridges – one from Rome to the island and one from the island to Trastevere. In the early days of Rome it took up to three days to haul boats up the Tiber from the sea to Rome. They had to use ropes and manpower or horsepower. The first bridges were wooden.

The bridges and the seven hills defined the city of Rome. The inhabitants fled up to the seven hilltops and burned the bridges whenever Rome was attacked. Only a few high spots were flood-proof; the river could rise as much as fifty-one feet during the floods that regularly occurred in the winter.In ancient times Tiber Island housed a temple devoted to Aesculapius, who was the Greek god of medicine and healing. In Christian times the site became home to a basilica dedicated to St. Bartholomew and a hospital. So, the island had been associated with medicine and well-being for approximately 2500 years by the time that we set foot on it.

Francesca told us that in Rome’s early days, people who had been healed sometimes left a small statue of the restored body part as a token of thanks and homage. This practice was still done today, but mostly silver plagues called “ex-votos” that denoted answered prayers were left as a tribute to the saint or relic that the person associated with the successful cure.

The island’s hospital, which was known as Fatebenefratelli, was run by the Hospitaller Order of St. John of God.[1] Francesca related that Roman women still preferred to give birth in this hospital.She then drew our attention to a banner with two crossed arms – one with a sleeve and one without. This was the sign of the Franciscans. The arm with the sleeve represented St. Francis in his habit. The one without a sleeve represented the Lord. Both hands clearly showed the stigmata.[2]

The island has long been connected to Rome by the Ponte Fabricio, which was built in 62 BC. This bridge, like many others, was littered with locks belonging to young lovers who affixed them to something permanent and then threw away the keys. The locks bore inscriptions pledging eternal love. In Italy the proliferation of this custom was largely due to a novel by Federico Moccia that was made into a very popular chick-flick. Francesca warned us that capers and figs were the enemies of architects. If left undisturbed for enough time, they inevitably destroyed the ancient buildings. The caretakers of the old structures must vigilantly prevent them from taking root.According to Francesca, Romans, more than other Italians, are very fatalistic. She hypothesized that that this might be due to the floods that were inevitable for so many centuries. In modern times the Romans had solved the flooding problem by building very high embankments. Unfortunately, the citizenry was now almost completely cut off from the river.

The plane trees that were a common sight in Rome were sycamores. The palm trees were not native to the area; they had been brought to Rome by Napoleon after his Egyptian campaign. They were now being gobbled up by an insect. No effective countermeasure had yet been discovered.

Records from the first century AD show that 60 percent of the population of the city was of foreign extraction. In those days to be considered a Roman one needed to be able to show that one’s ancestors were Romans for seven previous generations.

The current synagogue in Rome was constructed in 1904.[3] It was definitely an impressive structure, but we passed it without entering. It might have been interesting to discover whether it was as ornate as the Catholic churches.The Ghetto was constructed in 1555 at the order of the misanthropic Pope Paul IV. The wall was financed by taxation of the Jewish community itself! It was not torn down until the papal army was defeated in 1870. During the three centuries of the Ghetto’s existence, Jews were locked up within the walls every night, they were severely limited as to what occupations they could pursue, and they were forced to wear identifying garments.[4]

The emperor Titus destroyed the temple of Jerusalem in 73 AD. The legend that Jewish slaves had been used to build the Colosseum was probably not true, but many thousands of Jews were sold into slavery in the Colosseum.

Every papal doctor through the 1400’s was Jewish.

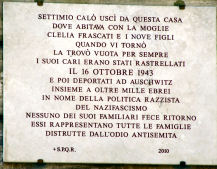

A piazza has been devoted to that date to insure that the citizenry will always remember what happened.

We passed by a building which was identified by the number twenty-five. I took a photo. Francesca said that it had been inhabited for about one thousand years.Tuesday was glass recycling day in Rome. We could hear the noise of rattling bottles from the trucks that were picking them up from the bins on the sidewalk.

Francesca was a little distraught at the sight of a street-sweeping truck that threatened to approach us and drown out part of her presentation. She said that she had hoped that illegally parked cars would prevent it from entering the area in which she had chosen to address us, but the path was clear. Nevertheless, she merely voiced a few minor incantations, and the noisy vehicle disappeared harmlessly into the depths of the city.As we passed a restaurant named Da Giggetto in the Ghetto, we stopped to appreciate the fresh produce that was outside on the sidewalk. A specialty of the neighborhood was fried zucchini flowers with anchovies and oil. Another was artichokes stuffed with garlic and mint and then deep-fried. Anchovies I understood; the rest sounded to me like food for fairies and elves, not people. Most of the group went inside to see how they prepared the dishes. I stayed out in the fresh air and snapped some photos.

In the Ghetto seven thousand Jews were crammed into four acres. The diabolical nature of this enterprise was really brought home to me when we came to Piazza Mattei, which is just outside of the original walls. Because the Matteis[5], who were related to the Hapsburgs, owned property that abutted the wall of the Ghetto at the entrance, the family was allowed to charge tolls for use of the gate! How incredible was that?

I accidentally dropped my pen while I was scrambling to take some photos. Francesca noticed, swooped it up, handed it to me, answered “Prego” to my “Grazie,” and never missed a beat of her presentation.Piazza Mattei centered around the fountain of the turtles, which was created by a Florentine artist in 1580. Romans were proud of the fact that the fountains and other wonderful pieces of art were not fenced off. The fact that they were so easily accessible to the public made them that much more precious to tourists who come from paranoid countries such as the United States.

On the other hand, Francesca proceeded to relate the cautionary tale of a vandal with a hammer[6] who in September of 2011 did some damage to the Moor Fountain in Piazza Navona. In 2011 the palazzo formerly owned by the Matteis housed the Institute for American Studies as well as lavish apartments. We went inside the courtyard of this building, known as the Palazzo Mattei di Giove. It was designed by Carlo Moderno to show off the wealth and power of the Mattei family. Francesca then gave a short disquisition on the Roman psyche, which she seemed to think was unique. She said that Romans suffered from a strange sense of hopelessness, in 2011 more even than at any time in the recent past. Most of them took their remarkable heritage completely for granted and exerted little effort to appreciate it. She complained that there was a lack of a healthy work ethic. One person had said that if the Italians had unemployment insurance, no one would ever work. Francesca opined that all Italians should spend six months of the year in the United States, and all Americans should spend half of the year in Italy. Where do I sign up?Italians have traditionally bought their houses or apartments; very few people rented. In 2011 a large number of young adults still lived at home because they could not afford to move out. Francesca recounted the sad story of a friend of hers who clung to a rather secure government job that would never pay her enough that she could afford to move to a place of her own. Tens of thousands of people must have been in a similar situation in Italy. She also told us that, years earlier, her father had felt insulted when she had informed him that she wanted to take a job as a waitress to help pay for her education.

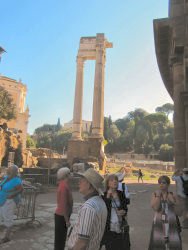

We stopped for a break when Rainer brought in some Pizza Ebraica for us to snack on. It was actually a type of sweet fruitcake. I found it quite tasty. Our next stop was the Portico d'Ottavia, named after Augustus’s sister who was married to Marc Antony. In the Middle Ages this area was used as a fish market. It then became the church of Sant'Angelo in Pescheria. There was also a cemetery there; some of the bones were still eerily visible. The entire structure was a hodgepodge of two thousand years of Roman architecture. The same could be said of the nearby Theater of Marcellus. In that case the upper stories of the ancient building had been converted into luxury apartments that could be purchased for $1 million or so. A “theater” in imperial times was always built in the form of a semicircle. The Colosseum was an amphitheater, which meant that it made a full circle from two facing theaters. Many of the ancient Roman buildings had been turned into ad hoc quarries in the Middle Ages. The workers burned the marble in order to obtain lime, which they could use in cement. Thank goodness the population had shrunk so drastically. If there had still been millions living in Rome, they almost certainly would have destroyed all of the ancient buildings. Francesca showed us where twelve feet of dirt had to be removed to reach the floor level of the original building. She also pointed out that on the right one could see an original column. The one on the left was revised. Next she related the familiar (to me at least) story of Cincinnatus, the farmer who was summoned from his agricultural labors to lead the Roman army in war. After his victory he returned to his field. Francesca said that pre-imperial Rome was originally terrified of civilization, which the Romans feared would lead to decadence. It took a few centuries for this hesitancy to be overcome by other desires.The Greeks always built their theaters on the side of a hill to take advantage of the slope. The Romans were able to employ arches to build them wherever they pleased. Francesca claimed that the events in the theaters and amphitheaters were akin to rock concerts or soccer games; the audiences were decidedly rowdy. Tomatoes had not yet been brought from the new world, so they threw rocks at actors whose performances fell short of expectations. They adored comedy, especially vulgar comedy.

Women were allowed to appear on stage, but only in comedies. The men and women both attended performances, but they sat in separate sections. Emperor Nero was an actor. He considered himself to be a talented thespian, even if few people agreed with his assessment.

The Victor Emmanuel II monument proved not to be very resistant to pollution. It was recently cleaned up for the sesquicentennial of the unification of Italy.

I was more than a little disappointed when the walking part of our tour ended, and we reached the famous ramp leading up to the Capitoline Hill. I could have gone on listening to Francesca’s ideas about Rome and Romans for the rest of the day or the rest of the week or … Never mind. The Capitoline had always been the most important hill in Rome. The generals returning from battle were brought there to receive their laurels. Prior to the Renaissance the buildings on the top of the hill always faced toward the Forum and the Palatine Hill, the centers of the civilian government. Michelangelo Buonarotti designed the current Campidoglio and the ramp leading up to the Capitoline Hill. He was employed by the pope, so he made it face toward the Vatican and St. Peter’s Basilica. This was no empty gesture; everyone understood that it meant that the pope was the capo di tutti capi in Rome.The piazza at the top of the Capitoline Hill was deliberately designed to be trapezoidal, not rectangular. It violated the architectural rules of the time, but it satisfied Michelangelo’s artistic sense. The famous statue of Marcus Aurelius was the only original equestrian statue remaining from imperial times. The one on display in the piazza was created in 1981. Francesca told us who was responsible for the pavement design, but I neglected to record the name.We took a bathroom break before entering the Capitoline Museums. An event was being held on the piazza for the UNICEF “Save the Children” fund. It involved a large number of kids and roughly the same number of red helium-filled balloons. My attention was drawn to a dozen or so young men clad in violet warmups who were obviously athletes. I recognized the distinctive color immediately. I was almost positive that they were members of the Fiorentina[7] soccer club, traditionally a contender in Serie A.

We learned that Pope Sixtus IV had donated the statues to the Capitoline Museum in the fifteenth century. The gigantic statue of Constantine was in pieces even then. When it was intact it would have been thirty feet tall. The emperor would have been sitting down and would have worn a metal crown. Only the extremities were made of marble.

Holes were clearly visible in the stone inscriptions that Francesca showed us. The indentations for the letters would have originally been filled with bronze.

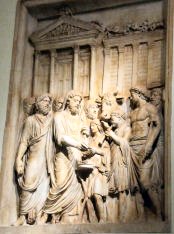

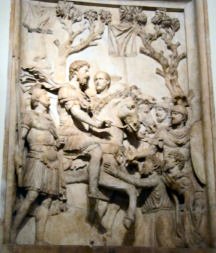

We spent some time learning to decipher the iconography of three bas reliefs of Emperor Marcus Aurelius. One showed him in a chariot. The second showed him on horseback with his arm extended in a peculiar manner. In the third his head was covered with a hood.Something in the depiction of Marcus Aurelius in the chariot was obviously wrong. He looked very unnatural because he was not standing in the center of the chariot. The explanation was that the piece originally included his son Commodus standing beside him. When Commodus later became emperor, however, he was so unpopular that he was eventually removed from the scene.[8]

The second piece showed Marcus Aurelius on horseback as the head of the conquering army. The defeated foes begged for mercy at the feet of his steed, and the gesture with his right arm was an indication of clemency. The third piece showed the emperor in his role of Pontifex Maximus, the religious leader of the Romans. The hood was symbolic of this function.

Francesca identified some statues of children as “yard art,” probably deployed in a way similar to the way that some Americans position statues of gnomes in their gardens.

We then got to view a see-through model of the gigantic Temple of Jupiter. Francesca explained that it was raised above ground level. The people were never allowed to enter the temple.

The Mediterranean Sea was undoubtedly full of priceless Greek sculpture. One out of five ships that sailed from Greece to Rome sank.

The museum had a whimsical display of female hairdos on display. These were wigs created by art students, but they were based upon what was known about how the Roman women actually wore their hair in the third century. Suffice it to say that many of them were elaborate enough to make Marie Antoinette envious. No photos were allowed of those exhibits.

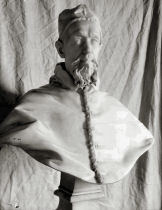

Thence we walked to the original statue of Marcus Aurelius. I took the obligatory photo. We viewed a unique statue of Commodus himself outfitted as Hercules carrying a club and wearing a lion skin, head and all. Bernini’s Medusa and Michelangelo’s death mask were part of the collection.

The Romulus and Remus statue was actually two works. The statue of the wolf was quite old, but the two youngsters were added later.

Ancient Romans liked to be portrayed either holding or standing beside a bust of their grandfathers or fathers. In addition, some families had hundreds of death masks that they would wear in funeral processions.

There were two huge statues of seated popes. Algardi depicted Innocent X in bronze. Bernini’s tribute to Urban VIII was in marble. The tour ended at a porch from which we had an outstanding view of the Forum, the Palatine Hill, and the surrounding area. I snapped a lot of photos. We all then gave Francesca a well-deserved round of applause.Rainer offered quite a few suggestions for lunch and for the afternoon activities, but I was not particularly hungry, and I already had an aggressive agenda for the afternoon.

He then buttonholed me and inquired as to when Sue and I would be available for a photo. I told him that I would certainly be around the hotel in the early evening, but Sue was unpredictable especially because of the situation with the Corcorans. I could tell that he considered the answer unsatisfactory, but I could think of none better.

I asked his opinion of my guess that some of Fiorentina’s players had been there in the morning as part of the UNICEF gathering. He said that the color was correct, but he doubted that the team would make an appearance in Rome. I tried to think of ways that I could check on it. I desired to visit four sites in the afternoon: Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, which was the home of the descendants of Pope Innocent X’s famous sister-in-law, Donna Olimpia, and three churches – St. Peter in Chains, San Luigi dei Francesi, and Sant'Andrea della Valle. If my path took me by the Pantheon, I would probably stop in there as well. I decided to walk up Via del Corso, the street created by Pope Paul II for his pre-Lenten games, to Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, which houses the Galleria Doria Pamfilj. When I reached Via della Caravita, I realized that I had gone too far. I extracted my Michelin guidebook and read that it was “In Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, entrance in Piazza Collegio Romano 2.” I retraced my steps and went down the alley to Piazza Collegio Romano. I was not sure what the “2” was supposed to mean, so I ignored it.

The piazza was full of schoolgirls. I found nothing that looked even vaguely like an entrance to a gallery. I went all the way around the block again and even searched the Piazza Collegio Romano again. Nothing. I went back to Via del Corso and was about to give up when I saw a very small sign for the Galleria. No one could possibly have found this place without luck and a good deal of effort. Evidently they had moved the entrance since the guidebook was printed.

I wanted to visit the museum because of my interest in Pope Innocent X, the only henpecked pope. I knew that it housed the awesome portrait of the pontiff by Velázquez and the famous bust of his sister-in-law, Donna Olimpia.I entered, paid €10 for an admission ticket that included an audioguide in English, and sat down in the courtyard to read the pamphlet that the clerk gave me. This gallery had three distinctly unique features:

- It had a superb audioguide that was written and narrated by Jonathan Doria Pamphilj, a descendant[9] of the people who built the palace.

- It was not crowded at all. As soon as I entered the courtyard, I felt as if I had instantly been transported to another world, and the feeling of pleasant detachment remained until I returned to the street.

- There were places to sit down in every room! After a long morning of walking and standing this was especially appreciated.

My biggest complaint was the dearth of written materials available. The audioguide was great but ephemeral. It would be really nice to have a written copy of the script. They did provide a small pamphlet with the names of the paintings. It also contained photos of a few paintings, but the resolution was not very good, and the images were small.

Jonathan, who actually lived in this palace as a young man, provided wonderful descriptions of what each room was used for. He even related how he and his sister had been reprimanded by their parents for roller skating in one of the rooms.I was especially interested in his take on the pope and his nephew, Camillo. The pope was under the thumb of Camillo’s mother, Donna Olimpia. He named Camillo as his Cardinal-nephew, which was the equivalent of Secretary of State. The real power, however devolved to Donna Olimpia. Eventually Camillo resigned as cardinal and married the widow Olimpia Borghese, formerly Olimpia Aldobrandini. This palace belonged to her. The couple had it decorated, and eventually they moved here. Their daughter married into the Andrea Doria family of Genoa. So, in the course of only two generations the obscure Pamphilj clan moved to the very top of Italian society.

The art collection seemed to be arranged by the size and shape of the paintings. Seriously. The objective seemed to be to fill every wall. However, the Velázquez masterpiece was provided with its own room. I was also very interested in the two busts of the pope by Bernini, the bust of Donna Olimpia by Algardi, and Caravaggio’s Rest After the Flight into Egypt. I would never have identified the last as a Caravaggio. It was much lighter and less stark than his later work.I was sorely disappointed with the bookstore. It had an impressive selection of books on art, including one that sold for €31 about the art of Pope Innocent X. There were no books about the history of this delicious period, however, or even about the history of the palace.

By the time that I left the gallery I was starting to get hungry. I had a long trek in front of me to reach the church of St. Peter in Chains. I consulted my map, but I was still not certain which was the best way to go. I decided to just walk up Via del Corso until I reached the Victor Emmanuel II Monument. Then I planned to hike up the Via dei Fori Imperiali to the Colosseum. I knew that the church was within a few blocks of the Colosseum.

I made a wrong turn at some point. I ended up going by a wax museum that had figures of Pope John Paul I and John Paul II in the window. The latter was easy to understand, but John Paul I was only pope for thirty-three days. Was there a lot of interest in him as a person? I got back on track. The Via dei Fori Imperiali was a terrible street for a pedestrian. It was noisy and crowded. There was nowhere to rest. I could find nowhere to pick up a bite to eat until I spotted a roach coach near the Colosseum. I purchased a bag of potato chips. I had a full water bottle.[11] I found a stone wall to sit on and enjoyed my repast, such as it was.I vaguely remembered that in 2003 after Sue and I visited the Colosseum with the tour group we ate lunch at a cafe that was a few blocks away. We intended to see St. Peter in Chains afterwards, but we were unable to located it easily, and we finally gave up. I had better maps this time. I did not intent to fail.

After I turned north from the Colosseum I soon came across a sign that jogged my memory. It showed St. Peter in Chains in one direction and the zoo, which is actually located in the Villa Borghese, in the other. We tried to find that zoo in 2003. Someone finally told us that it was a long way away. I could not fathom why that sign would still be there eight years later. I knew that I was close when I came across the the cafe in which Sue and I had eaten lunch eight years ago. I remembered that it was over eighty degrees out, and we were offered a free cup of coffee at the end of the meal.I eventually did find St. Peter in Chains and, mirabile dictu, it was open. I went in and took the required pictures of the church and the chains that supposedly bound Peter. The links were much larger than I expected. They looked like chains for an elephant.

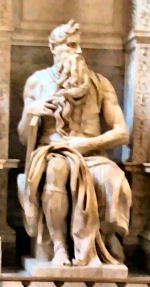

What I really was interested in was Michelangelo’s tomb for Pope Julius II. It bowled me over. The statue of Moses was awesome. The horns were a little hard to understand, but Michelangelo definitely knew how to show a powerful physique.The contrast with the rendition of the pope as a figure lounging on his side was mind-boggling. Could Pope Julius, who wore armor into battle even after he became pope, have approved this? Surely not. I had heard that when Michelangelo did another sculpture of him, the artist had decided to portray him with a book. The pontiff insisted that a sword was more appropriate for the most militaristic of all the pontiffs.

Who was this layabout, and what had they done with the real Pope Julius II? I could only conclude that Michelangelo must have portrayed him like this out of revenge for the way that the pope who would not take “No” for an answer had treated him. I was certainly glad that I got to see this with my own eyes. I decided to try to take a shortcut back. Some side streets led me up and down some pretty steep hills. I probably actually walked farther than I did on the way over. At least it was a more pleasant walk. I was shocked when I came across a store called Barbiconi that sold nothing but vestments and other accoutrements for priests and bishops. The store had two entire display cases filled with items for bishops! What other town could support such a store?I finally came across a sign for the Pantheon and Santa Maria Sopra Minerva. I almost walked past the Pantheon because I thought that it was Santa Maria Sopra Minerva.

I made a very quick stop inside the Pantheon. It was impossible to think of it as a church. I took a photo of the Oculus. I also located the tombs of Victor Emmanuel II, Umberto I, and Raphael. I was puzzled by the sculptures of birds over Raphael’s tomb.

I was pretty sure that by this time the church of San Luigi dei Francesi would be open. As I approached the church I thought that I saw Judy exiting. I remembered that she had said that she was a big fan of Caravaggio, and the primary attractions of this church were the three outstanding Caravaggios. I took a few shots of the interior of the church and then headed for the chapel that housed the Caravaggios. I was shocked to discover that not only were the paintings illuminated, they even allowed photography. There were quite a few people, so it was not easy to take a great shot, but I managed three tolerably good ones.

I was exhausted. If the church of San Andrea della Valle had been even one block out of my way, I would have just gone back to the hotel and collapsed on my bed. However, it required almost no effort to go into San Andrea, so I did so. The interior was exceptionally beautiful, and Domenichino’s painting of the saint’s crucifixion was nothing short of stunning.

I had a very difficult time finding the tombs of the two Piccolomini popes, Pius II and Pius III. The Michelin guide said that the tombs “lie above the last bay in the nave before the transept.” I found the last bay without any problem, but I could find no sign of the tombs other than a piece of paper that described in Italian the one devoted to Pius III. I knew that I must be close, but where could they be?

Finally, it occurred to me that when the guide said “above” it literally meant up in the air. Sure enough, the tombs were embedded in the wall some twenty feet off of the ground. They were not in the least impressive, but I had such a hard time locating them that I felt obligated to photograph them.

I then walked back to the hotel. Sue was there. I looked for Rainer, but I could not find him. Sue and I took a photo of ourselves with my camera. Sue then downloaded it and e-mailed it to Rainer.

I asked Sue what she had done during the day. She told me that the power in the room had gone out. She reported the problem, and the man at the desk said that he would address it, but hours went by before the lights came back on.

Sue explained that she had spent most of the day with Tom at the hospital. Patti’s condition had not stabilized enough that the doctors were ready to release her. On the other hand, they had not admitted her either. She was still in Pronto Succorso. I did not understand that, but I was not familiar with Italian medical procedures.

Sue and Tom had eaten lunch at La Famiglia. They reportedly had had a pretty good time there, but Sue’s videocamera had begun to misbehave. It had a short or something that caused the screen to malfunction. The result was that Sue no longer knew when it was recording, and whenever it was functioning she was not certain what it was recording. Tom had checked out of the Hotel Selene and was now staying at a hotel closer to the hospital.One thing was certain; Sue was not having much of a vacation. She was spending all of her time helping other people with their problems. This was exactly what she did most of the time at home.

Sue thought that we should go visit Tom and Patti this evening. Maybe it was our obligation to do so, but I needed to get some rest first. Then when I felt a bit revived, I became very hungry. My only food since breakfast had been the bag of chips. The bottom line was that I really was not in the mood for corporal works of mercy. In retrospect, that was probably a selfish attitude.

Sue and I went out for supper. I thought that I could find L’Antico Moro without difficulty, but I never did. After wandering the twisted streets of Trastevere long enough to make Sue’s knees complain, we sat down for a minute at one restaurant, but the prices were outrageous. I became upset that we could not find a decent place. It seemed so easy last evening. I should have just looked L’Antico Moro up on the Internet; it would have taken five minutes. I suppose that I could have asked someone, but guys did not generally resort to that strategy unless they were desperate.

We ended up at a little pizza place named Casetta di Trastevere. I had my usual Italian meal of sea food with pasta. This restaurant called it Spaghetti Caroccio, or something like that. Sue had mixed vegetables, which turned out to be mostly fried eggplant. We both thought that the food was not bad, and it was not expensive.We shared a table with a couple from Montreal. He spoke English, but she did not. The waitress brought her pizza but forgot to bring his meal. The waitress eventually rectified the situation, but by that time she was almost finished with her pizza.

I was too exhausted to think about going to the hospital. I felt pretty sure that Sue was disappointed in me. After all, we had been friends with the Corcorans for thirty-nine years.Aside from the awful situation with Tom and Patti, I was pretty well satisfied with our sojourn in Rome. Sue was still on her feet, which was about as much as I could expect. I had endured some disappointments during the first few days in Rome, but this day was perhaps the best day that I had ever had on a tour. I learned, saw, and photographed so much that I could hardly digest it.

On the other hand, we definitely would need to come back to Rome. We had hardly scratched the surface of this incredible city. Six or eight months more might do it.

[1] This order was founded to help people in the Crusades. Sue and I visited its home base in Rhodes in the nineties. The Hospitallers also played a crucial role in the incredible story of Djem.

[2] My understanding is that no contemporary of St. Francis ever mentioned the stigmata in writing. He personally met with Pope Innocent III, and the pope, a prolific correspondent, never mentioned the wounds.

[3] During this period (1870-1929) the popes were pretending to be prisoners in the Vatican.

[4] Yes they were treated badly, but they were not burned as heretics, and plenty of Christians were. The popes could not understand why the Jews complained about their condition.

[5] I had never heard of this family. It produced numerous cardinals but no popes or even papabili that I knew of.

[6] From what I have read, he used a cobblestone, not a hammer.

[7] The red fleur-de-lis insignia is the clincher. Also, the club has had a long association with UNICEF.

[8] What a contrast to the attitude of the people at St. Paul’s who never bothered to remove two fictitious popes and an antipope who was convicted of five felonies.